Use Pattern Management at any time to improve glucose control. Remember that this becomes most effective once your TDD is relatively appropriate and you program more accurate basal rates, CarbF, and CorrF into your pump. Optimize your settings first! Check any new pump settings after you live with them for a week or so to see how they work. You then have CGM data from which to work.

Pump settings need adjustment from time to time as life changes. For example, your TDD and settings often need to provide slightly larger doses in winter and slightly smaller ones in summer. Change is the only constant in life, so if your management worsens over time or you want to fine-tune your settings to the next level, pattern management can help you.

Nowadays, a CGM makes it easy to see patterns. If you don’t have a CGM, frequent testing with a meter and graphing your results works well when combined with a graphical recording method like the Smart Charts.

Go Here if you are unfamiliar with an abbreviation or term.

You can use a CGM to improve readings in two ways:

- In Real Time. Work here to increase your time between your target lines. Actively respond to the data on your CGM screen:

-

- Increase your basal rates or bolus doses or reduce carbs, as needed, to stay below the upper glucose target.

- Decrease basal rates or carb boluses or increase carbs to stay above the lower target.

- After you give a bolus, monitor your IOB (insulin on board that remains active), glucose, and its direction and rate of change on your CGM. Respond with carb intake if IOB is excessive or by taking a correction bolus if it is inadequate to bring down the glucose.

-

- From a CGM download. CGM data clearly shows that basal rates, boluses, and lifestyle improvements are needed. See Glucose Goals.

Pattern Recognition

Look at your graphs and data objectively. Emotions tend to cloud vision. If it helps, pretend they belong to a friend or family member. At times, we’re like old horses, taking the same route repeatedly, even though it’s become rocky and treacherous. Take off the blinders, get on the saddle, look with clear eyes, and help yourself live a better life.

Here’s an Example of a Good Avg Glucose and Low CV (Where You’d Like to Head):

Compare It to These Unwanted Patterns You Will Be Looking For:

- No Apparent Glucose Pattern: All Over the Charts

- Most Common Glucose Pattern: High Glucose at Night, Not Much Delight

- Frequent Lows: Deep Sea Diver

- Frequent Lows at a Particular Time of Day: Snorkeler

- Lows from Over-Correcting Highs: Sky Diver

- Frequent Highs but Relatively Flat: High Flyer

- Frequent Highs with Post-Meal Spiking: A High Tide Raises all BGs

- Frequent Highs at a Certain Time of Day: Kite Surfer

- Before Breakfast Highs: High in the Morning, Take Warning

- Highs after Over-Treating Lows: Rocketeer

- Post Meal Spiking: Big Waves

Now that you’ve seen all the patterns compared with one another let’s take each one at a time and look at ways to resolve each one:

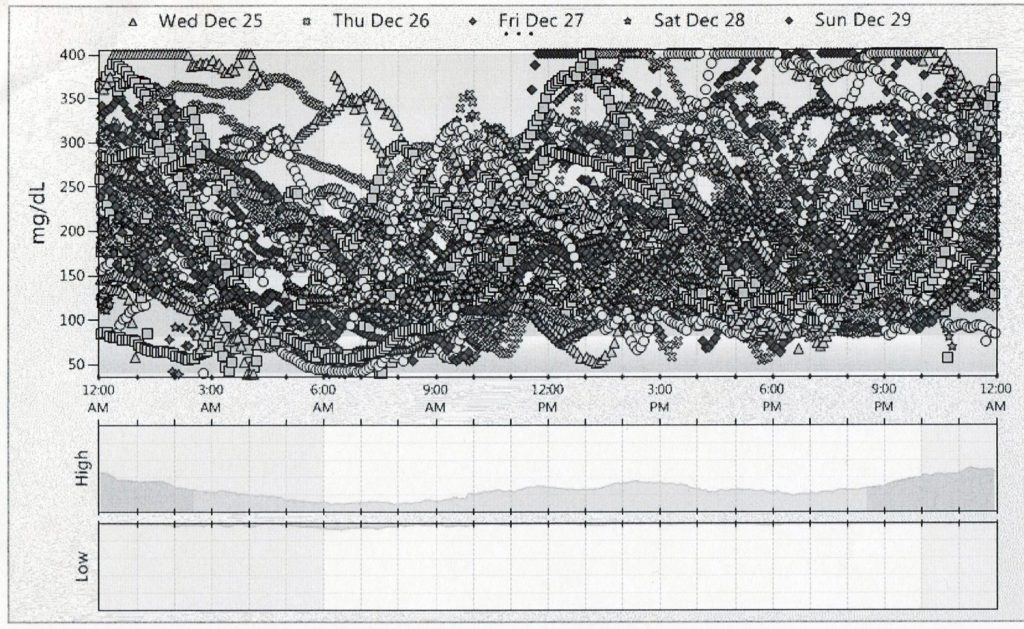

1. No Apparent Glucose Pattern (All Over the Charts)

Erratic glucose readings that seem to have no rhyme or reason have four familiar causes:

- TDD Too Low: A low TDD or small carb boluses cause high glucose readings throughout the day. Correction boluses only temporarily bring them down. See Pattern #6 or #7 to increase your TDD for faster adjustment of your pump settings with AID and Pump Settings Tool.

Here, the TDD is too low, evidenced by the high avg. glucose of 263 mg/dL and having 76% of the readings above 180 mg/dL. The basal rates appear to be too low as shown by the rise in glucose starting at 4 am. Post-meal glucoses are rising especially at lunch and dinner, suggesting that the CarbF number needs to be lowered OR retraining is needed to bolus before all meals. - TDD Too High If frequent lows are frequently over-treated, erratic readings also result. Here, you would reduce the TDD to stop the numerous lows first. Avoiding overtreatment of lows can also be quite helpful. Decrease your TDD by 5% or 10% and modify your pump settings with the Pump Settings Tool.

- Bolusing late or not at all results in erratic glucose readings. Take boluses early before the meal and improve accuracy based on carb counts, checking your CarbF, and direct feedback from your CGM screen, Bolus 15 to 30 minutes before meals or substantial snacks whenever possible. When glucose goes low before a meal, consume quick carbs and then cover the remaining meal carbs with a regular carb bolus.

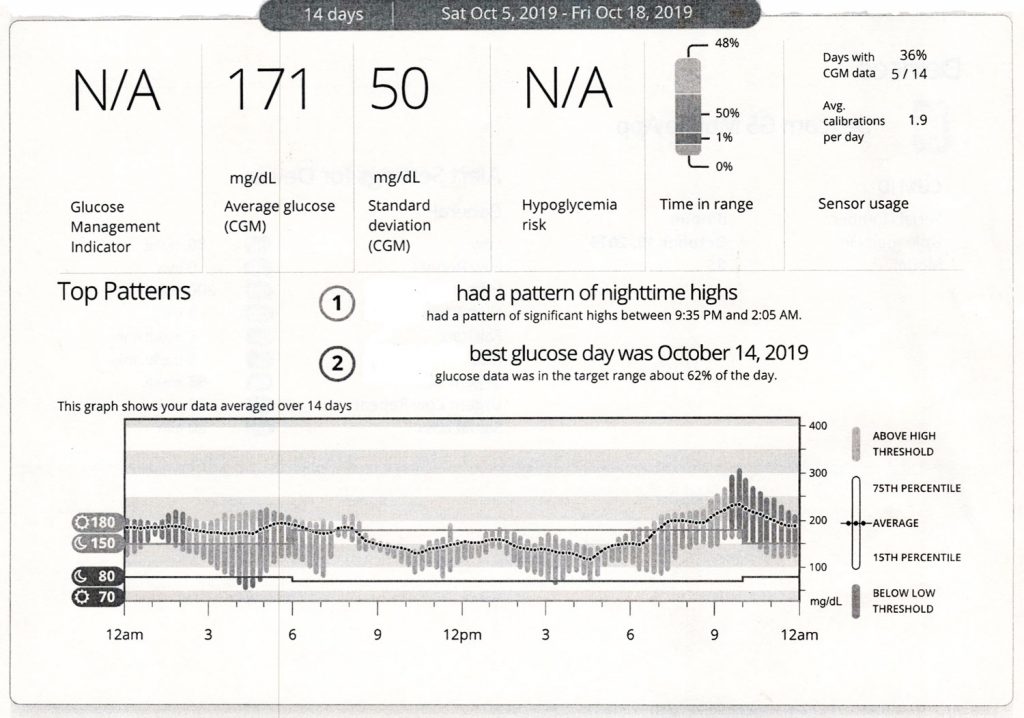

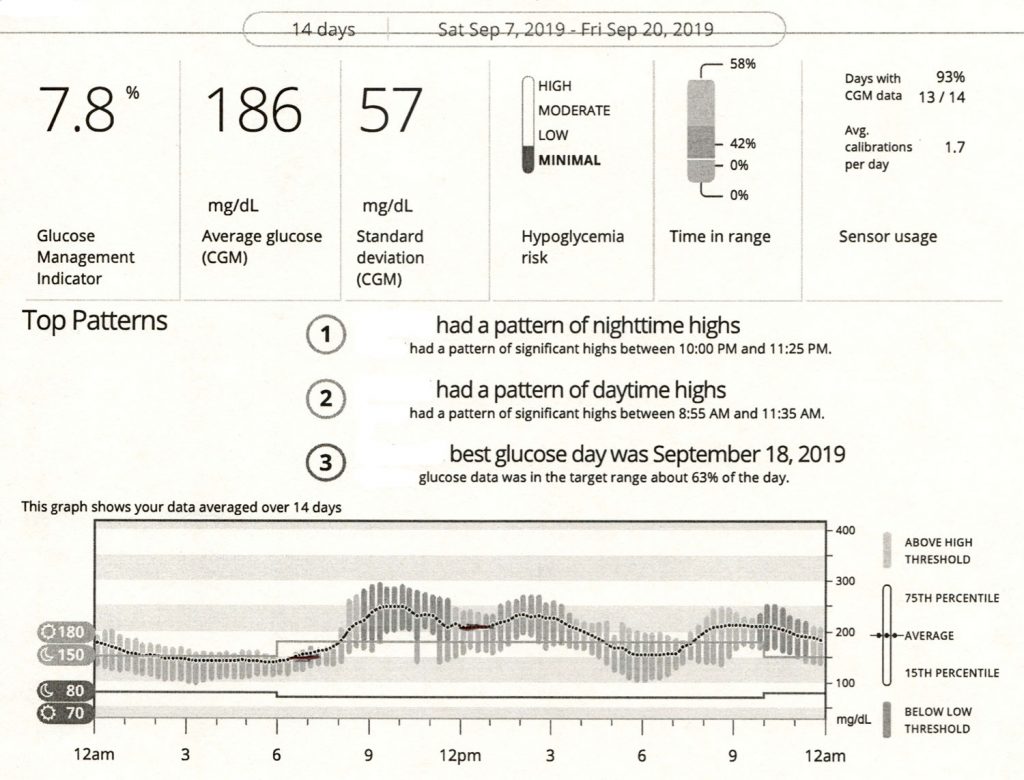

2. Most Common Glucose Pattern (High Glucose at Night, Not Much Delight)

The most common glucose pattern below shows readings that are lower during the day, then rise after dinner and stay high into the early morning hours.

- Here, raise the mid-afternoon through evening basal rates and lower the dinner CarbF.

- Fear of nighttime lows can make this mentally challenging to correct. To counteract fear, get and wear a CGM, or better yet, get a full AID. (Fear of hypoglycemia is one of the criteria your doctor can use so your insurance company will cover a CGM or AID.) Use the CGM to verify your night basal rates: Look at your CGM when you wake up in the morning to see if your glucose stayed relatively flat overnight, starting 5 hours after your last bolus the night before.

Always check for IOB before bed, and make sure to set your DIA to 4.5 hours or longer.

3. Frequent Lows (Deep Sea Diver)

Common Causes for Frequent Lows and What to Do

When your readings frequently go low, such as below 60 mg/dL four or more times a week, either:

- Your TDD is excessive (basal rates are too high, CarbF or CorrF is too low). This is suggested when frequent lows occur at different times of the day and are unrelated to increased activity. Unlike too little TDD, which is comparatively easy to increase based on your average glucose, the number of excess units in the TDD when lows are frequent can only be determined by gradually reducing the TDD:

- Decrease your TDD by 5% for frequent mild to moderate lows, such as ones that don’t go below 55 mg/dL.

- Decrease your TDD by 10% for frequent lows below 55 every 2 or 3 days.

- You are receiving too much insulin from one of your doses. This is suggested by a pattern of frequent lows at about the same time of day. Examples include low glucose before breakfast from excess basal rates or long-acting insulin or lows before dinner from the lunch bolus.

- If many lows happen at about the same time of day, lower your basal rate about 5 to 8 hours earlier or raise your CarbF number for the previous meal. The one to adjust is usually the one that is giving you more insulin during the last 5-hour period.

- Your CarbF or CorrF number is too small. This is suggested when low glucose readings occur within 2 to 5 hours after blousing for meals or high glucose readings.

- A short DIA or AIT time hides insulin stacking.

- A pump or AID does not subtract IOB from carb boluses.

- Or you can take correction bolus larger than the recommended dose.

Managing your glucose becomes greatly simplified once you stop frequent lows.

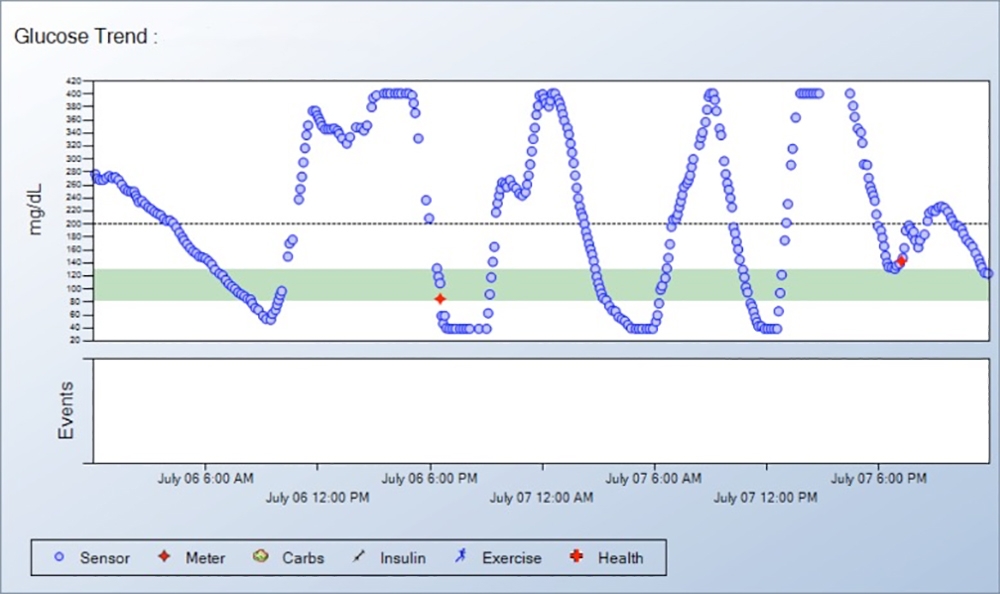

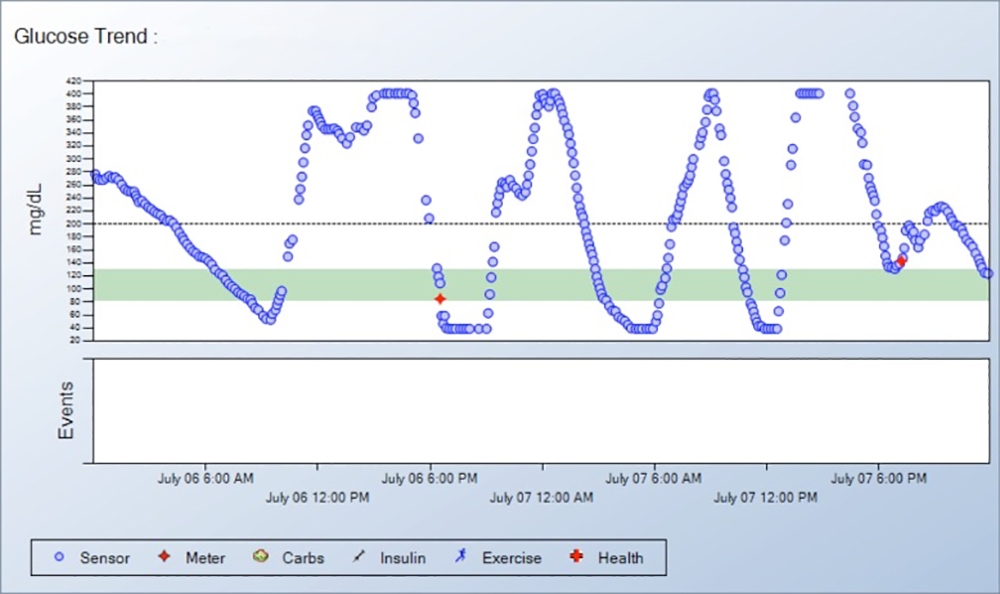

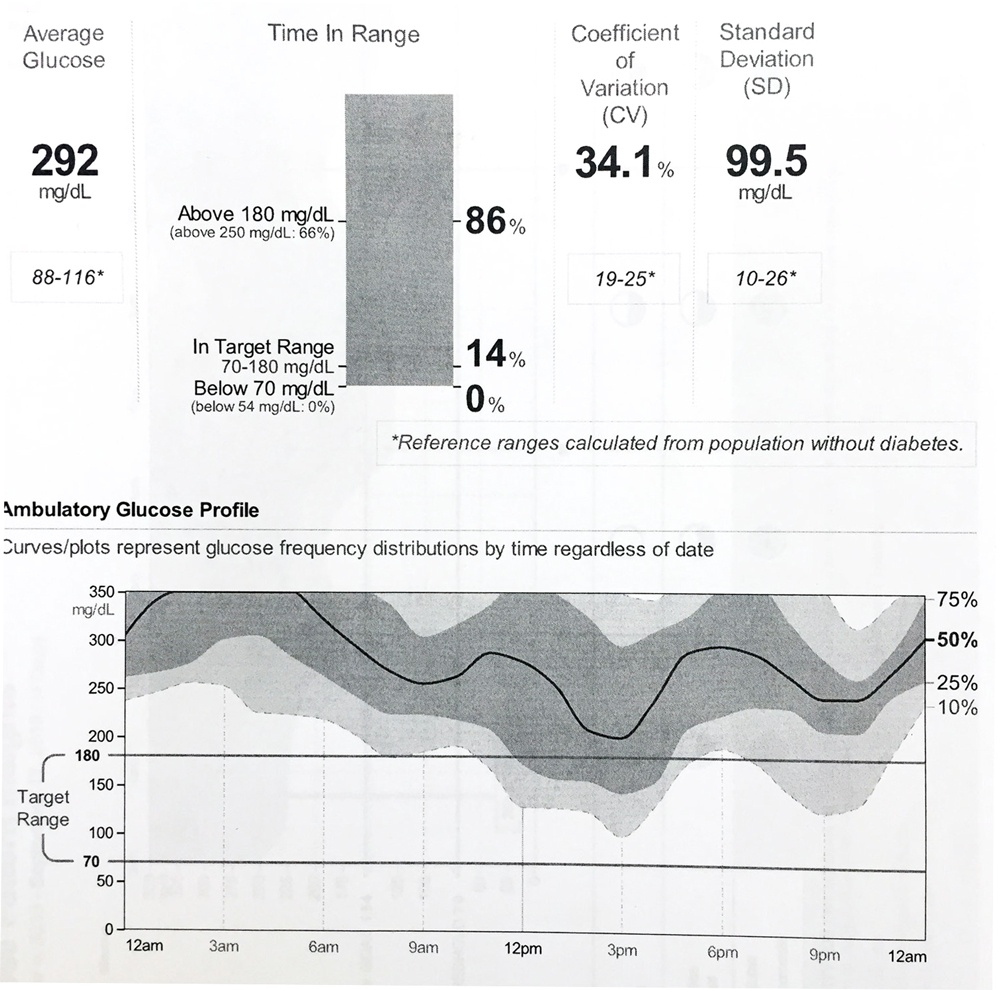

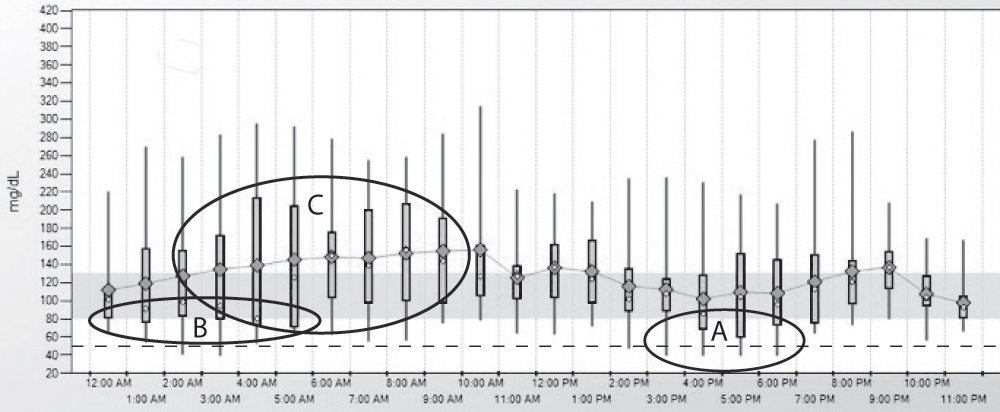

| 13.5 Frequent Lows on CGM |

|---|

|

This person has frequent severe lows between 4 and 6 pm with 25% of the readings at A below the 50% boxes and the lowest glucose lines extending below the horizontal dotted line at 50 mg/dL. Other low readings can be seen at B, followed by erratic readings in the early morning hours as shown by the tall 50% boxes at C. |

4. Frequent Lows at a Certain Time of Day (Snorkeler)

- Lower the basal rate slightly 5-8 hours before the low happens, or raise the CarbF for the previous meal if lows typically occur within 5 hours of the meal bolus.

- If hypoglycemia happens only after the glucose before the previous meal is elevated, consider raising that CorrF number to reduce the size of correction boluses.

Figure 13.6A gives additional tips.

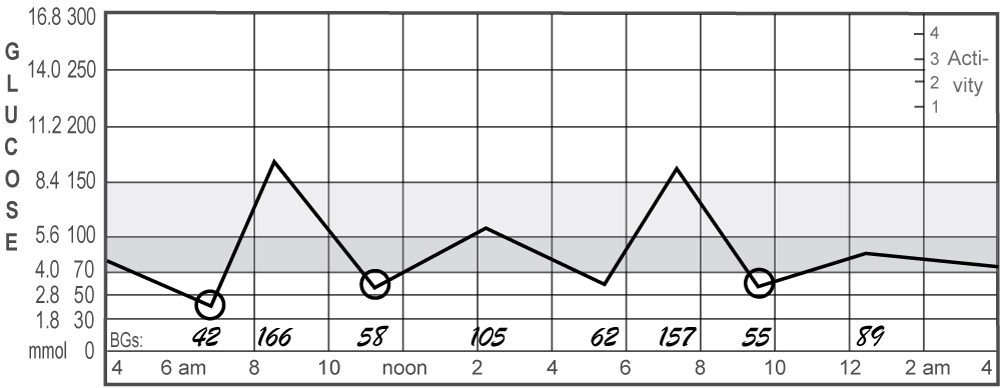

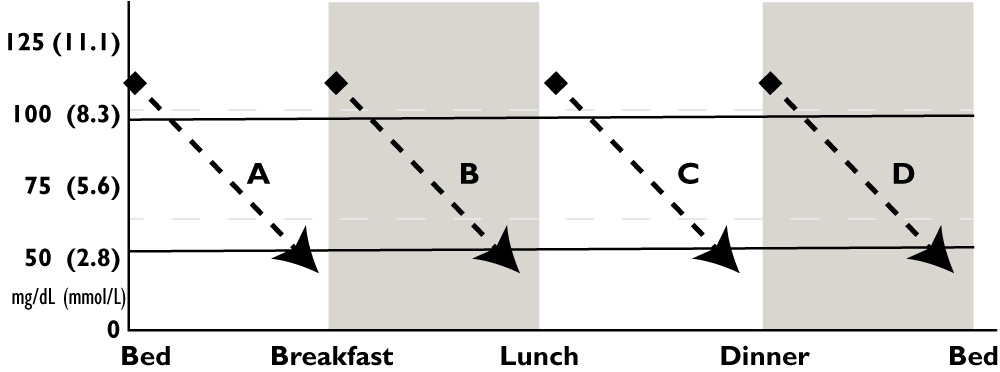

| 13.6A How to Stop a Pattern of Lows at a Particular Time of Day |

|---|

|

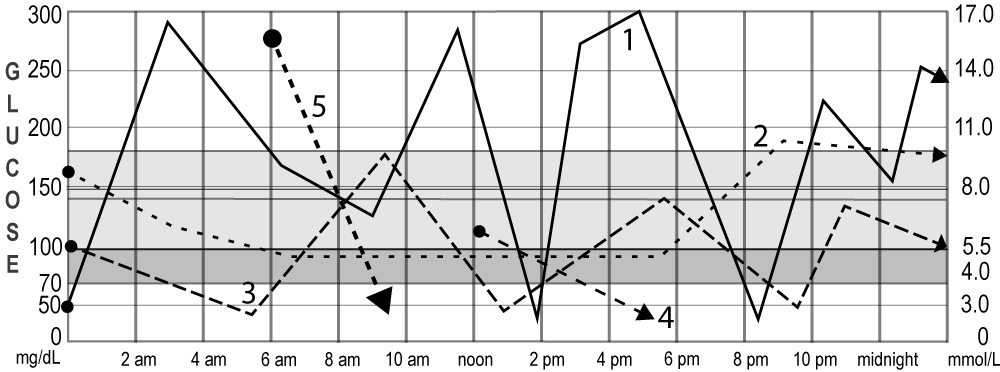

Look below for the time of day when your glucose typically goes low, then try one of the corrections suggested for that letter. For example, if your glucose goes low between breakfast and lunch, look at B for suggested solutions.

|

To figure out which insulin to adjust, add your carb and correction boluses taken in the last 5 hours (include any IOB at the start of the 5-hour period that is still working from an earlier bolus). Compare this to the basal units for 5 hours(multiply your hourly rate by 5). Adjust whichever is larger.

A. Pre-breakfast lows

An excessive overnight basal rate, or long-acting insulin dose, is usually the cause. Lower your basal rate starting before midnight. Use a small reduction for occasional mild lows and a more substantial cut for frequent severe lows.

Other causes for low readings include excess exercise or starting a new exercise regimen, rage boluses, bolus delivered but carbs not eaten, excess alcohol intake, or starting a diet. Avoid self-induced highs from high GI foods, bolusing after meals, insufficient basal rates, or inaccurate carb counts.

Middle-of-the-night lows

- Your basal rate after dinner may be too high.

- The CarbF number at dinner may be too small and make boluses too large or

- The CorrF number near bedtime might be too low.

- Always account for any excess IOB at bedtime and take carbs to cover this. When you bolus for a bedtime snack, subtract any excess IOB from the bolus you take. See Insulin Stacking.

- More than two standard drinks of alcohol can also cause night lows.

5. Lows from Over-Correcting Highs (Sky Diver)

If lows often happen after giving a correction bolus for highs:

- Increase your Correction Factor (CorrF) or ISF number to reduce the amount of insulin you get as a correction.

- Ensure your DIA or IAT is set to 4.5 hours or longer to eliminate hidden insulin stacking.

- Be patient and wait long enough for the correction to work. Avoid rage boluses – ‘Take THAT, blood sugar!” Rage boluses only cause lows. Entering 10 grams of carb with the correction bolus is a safer way to speed up corrections. Just monitor your CGM and consume 10 grams before you go low!

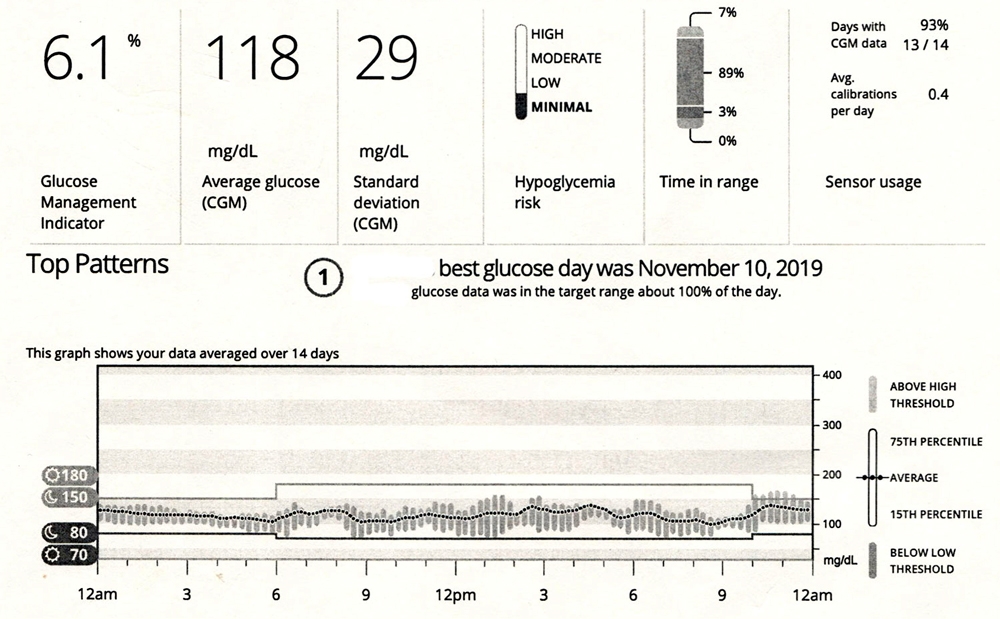

6. Frequent Highs but Relatively Flat (High Flyer)

The good news? At least you’re steady.

The bad news? You’re too high.

Again, this is a straightforward fix. Increase your TDD. Usually, a simple increase in the basal rates or long-acting insulin will lower these readings significantly. For a conservative increase in the TDD, use the AID and Pump Settings Tool, then try the new basal rates and pump settings from the new TDD.

- Raise the TDD by 5% for every 1% reduction desired in the A1c, e.g., If the A1c is 10.0% and the target is 7.0%, 10% – 7% = a 3% lower A1c x 5% = a 15% increase in the TDD, for an average TDD of 40 u/day, the new avg. TDD would be 40 u x 1.15 (or 115%) = 46 units a day.

- Or raise the TDD by 1% for every 6 mg/dL reduction desired in the average glucose, e.g., if the average meter glucose is 200 mg/dL and the target is 140 mg/dL, (200 – 140) = 60 / 6 = a 10% increase in the TDD. For an average TDD of 40 u/day, 40 u x 1.1 (or 110%) = 44 units as the new TDD. (A CGM’s average glucose can be trusted; a meter average can mislead if the user treats but doesn’t test when low, tests on other meters, etc.)

- You can also check your glucose 6-8 times a day or enter CGM values frequently into the bolus calculator and give correction boluses as recommended. After 7 days, use the new 7-day average TDD to select better pump settings. Repeat if needed.

- Another helpful trick is not to eat until your glucose is below 140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol) – This can be a great motivator for rapid adjustment of pump settings!

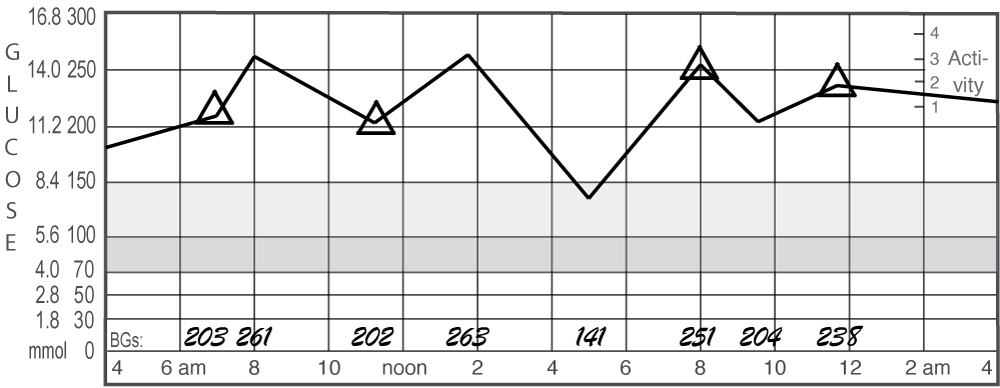

7. Frequent Highs with Post-Meal Spiking (A High Tide Raises All BGs)

Increase the TDD using the AID and Pump Settings Tool and then calculate new basal and bolus amounts from the new TDD.

For each 6mg/dL drop desired in average glucose, increase the TDD by 1%

Example:

Your average glucose is 200, and you want it to be 140 for a 60 mg/dL drop.

So, 60 divided by 6 = a 10% rise in the TDD.

If the TDD is currently 40 units, multiply it by 1.1 (110%) to make it 44.

Also, take a look at your basal/carb bolus balance. If one or the other is a good deal more than 50% of the TDD, raise the other one first to meet it.

For tips on avoiding going high after meals, see Post-Meal Spiking.

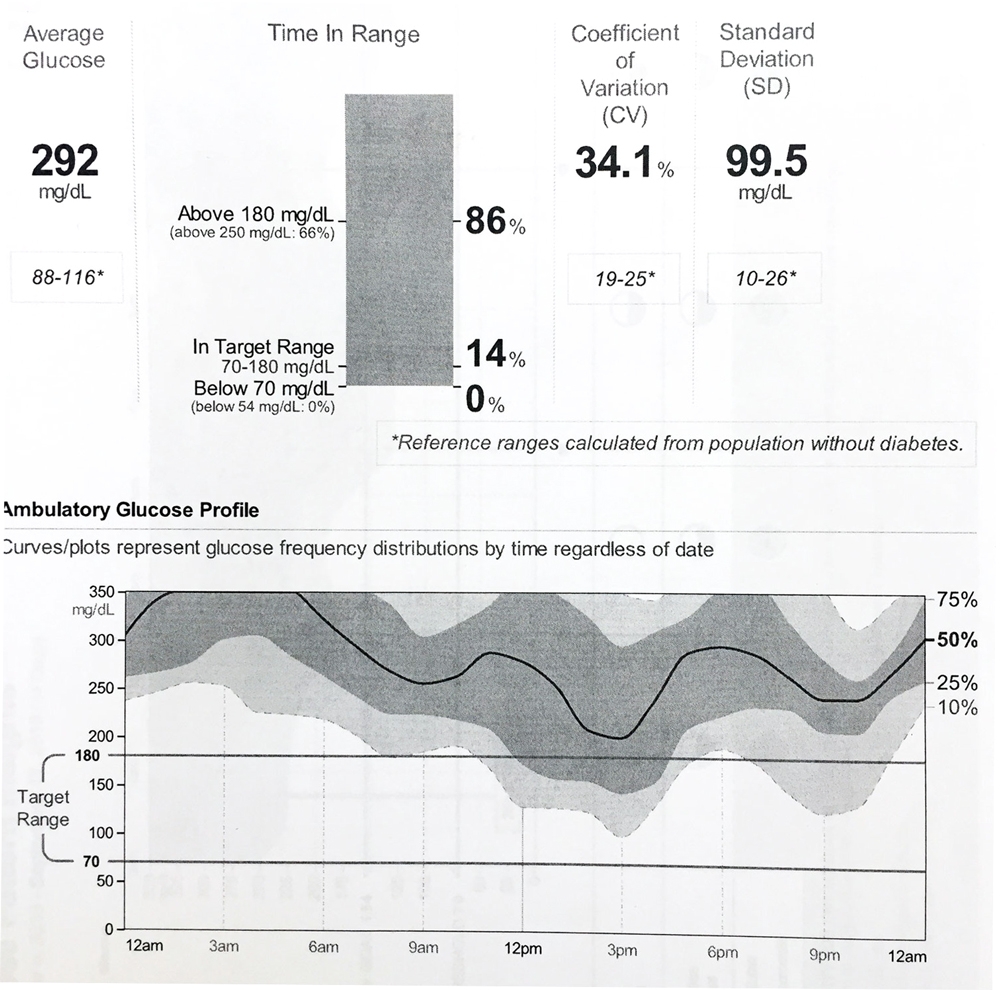

292 mg/dL minus 140 mg/dL = 152/6 = a 25% increase needed in the TDD. This person can multiply their TDD by 1.25, from which new pump settings can be obtained, or by entering their average TDD and glucose with their weight in the Pump Settings Tool.

8. Frequent Highs at a Certain Time of Day (Kite Surfer)

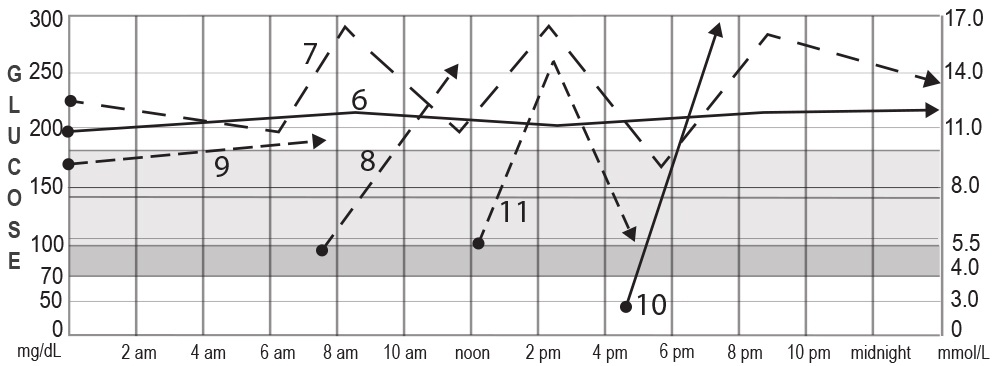

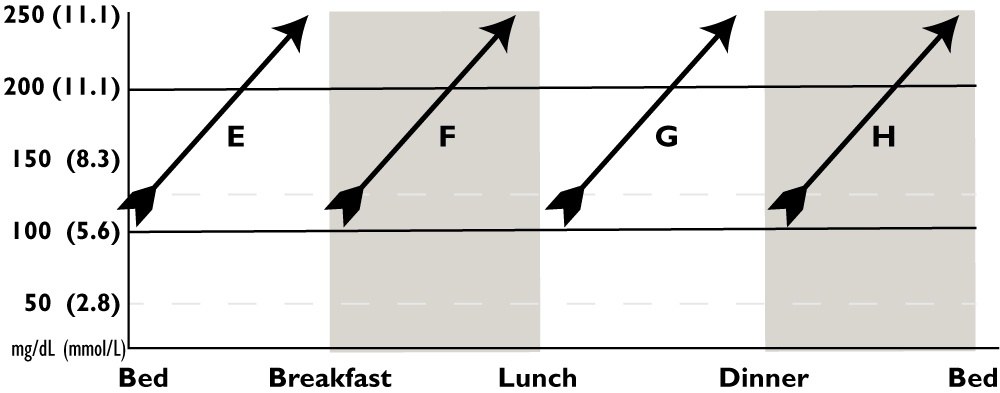

| 13.6B How to Stop a Pattern of Highs at a Particular Time of Day |

|---|

|

Look for the time of day when your glucose typically rises to a high glucose, then try one of the corrections suggested for that letter. For example, if your glucose goes high between breakfast and lunch, consider F for suggested solutions. E) If the glucose usually goes up between bedtime and breakfast, raise your basal rate overnight or at least 2 hrs before the glucose starts to rise. (See H if your glucose is usually already high at bedtime.) F) Lower your breakfast CarbF or raise the basal rate(s) 5 to 8 hours earlier. G) Lower your lunch CarbF or raise the basal rate(s) 5 to 8 hours earlier. H) Lower your dinner CarbF or raise the basal rate(s) 5 to 8 hours earlier. Consider whether after-dinner snacks cause the rise. |

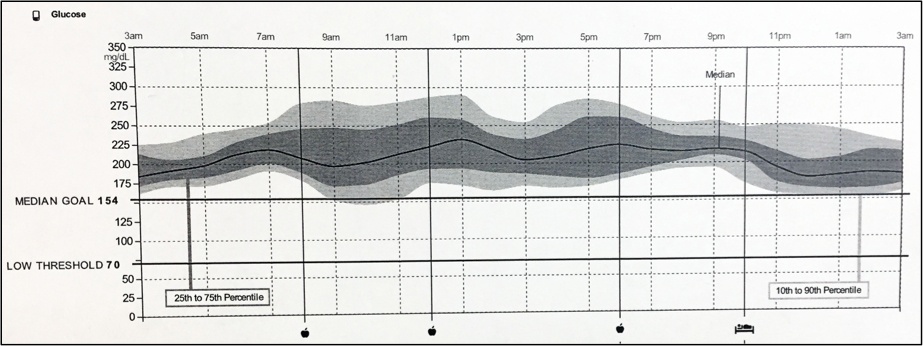

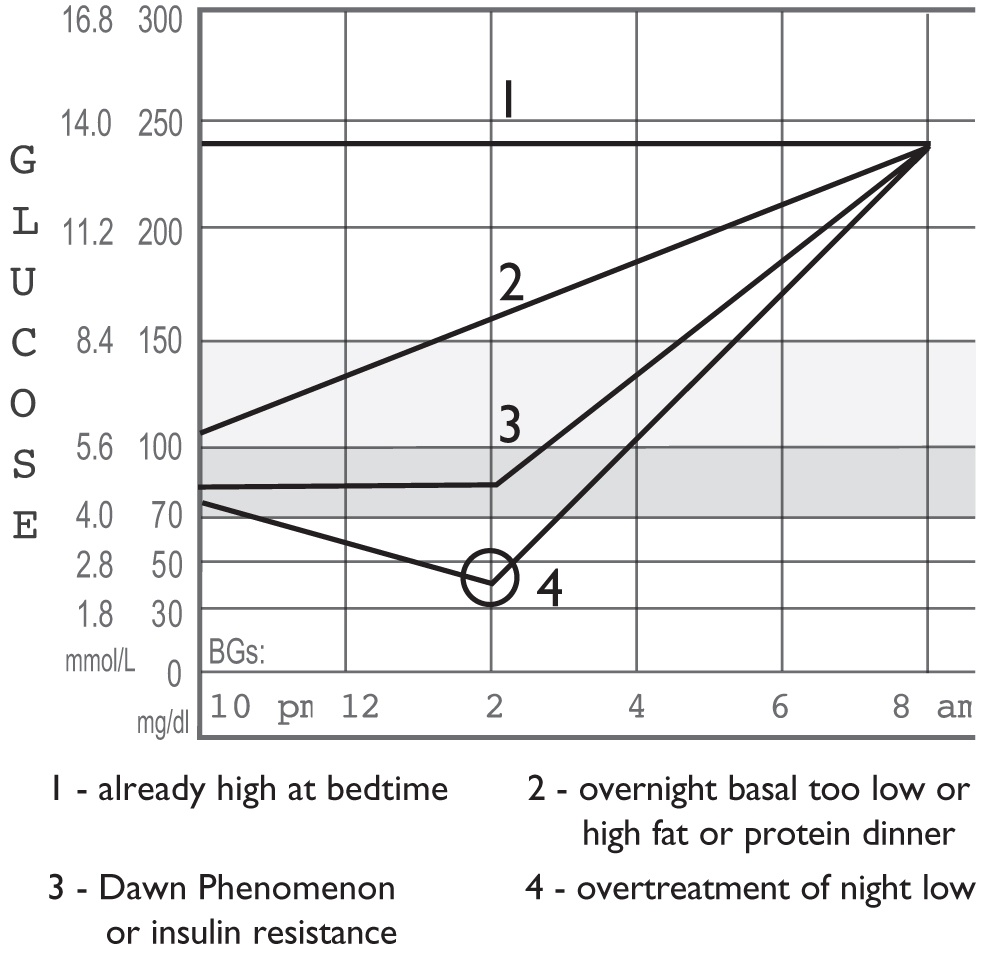

9. Before Breakfast Highs (High in the Morning, Take Warning)

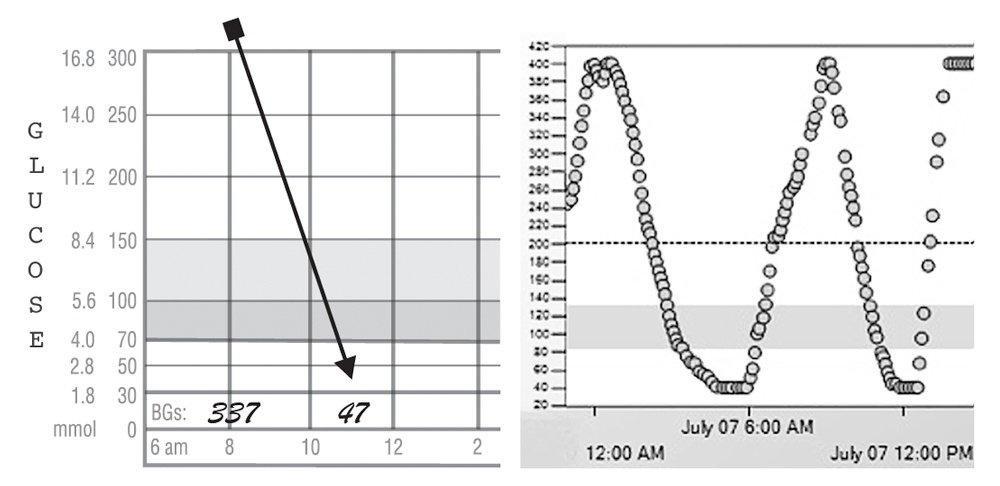

Morning highs are critical to fixing. When they have been high for hours overnight, your A1c is higher, and you need larger correction bolus than usual to bring the glucose down. Once pre-breakfast readings are great, the rest of the day becomes far easier to manage. The graph below presents four different causes for highs before breakfast.

A. Already High at Bedtime

- Here, the glucose rises after dinner and stays high all night. Always fix bedtime highs first when they are the source for breakfast highs.

- Increase the afternoon and evening basal or lower the CarbF for dinner to eliminate bedtime high readings. This is invariably safer than taking a correction dose right before going to sleep.

- If you usually give correction boluses at night, but your glucose stays high overnight, you need to raise the evening and nighttime basals or lower the bedtime CorrF.

B. Night Basal Too Low or Dinner/Snack High in Fat or Protein

- If the glucose rises during the night between bedtime and breakfast, the night basal rate is too low. Raise the late evening and overnight basal rates by small amounts, starting 2 to 3 hours before the glucose begins to rise.

- If the night glucose is rising because of big bedtime snacks eaten due to fear of going low overnight, retest and reset the nighttime basal until it stays flat, then trust your testing and lower your bedtime grocery bill.

- If your glucose is often low at bedtime, correct this pattern, and remember not to over-treat lows.

- If this pattern occurs only after eating a dinner of unknown carb quantity or dinner that is high in fat or protein, such as many restaurant meals, see How to Bolus for Fat and Protein.

C. The Dawn Phenomenon or Insulin Resistance

In teens and young adults, a circadian release of growth hormone can cause the liver to release extra glucose starting in the early morning hours. This makes the breakfast glucose high and requires a larger than normal correction bolus to counter the excess glucose release.

- An increase in the nighttime basal starting at about midnight or 1 am helps block the liver from releasing excess glucose. The earlier you raise the basal rate, the smaller the rise needs to be.

- A prescription for metformin is also a great way to block the excess release of glucose from the liver. This lowers insulin requirements and tends to make teens feel better when they wake with more normal readings on metformin.

| 11.2 How to Change the CarbF (ICR) | |

|---|---|

| If Current CarbF is: | Adjust up or down by: |

| Less than 5.0 gr/u | +/- 0.2 to 0.3 grams/u |

| 5-10 grams/u | +/- 0.3 to 0.5 grams/u |

| 10-15 grams/u | +/- 1.0 grams/u |

| 16-24 grams/u | +/- 1 to 2 grams/u |

| Larger CarbF changes are occasionally needed. | |

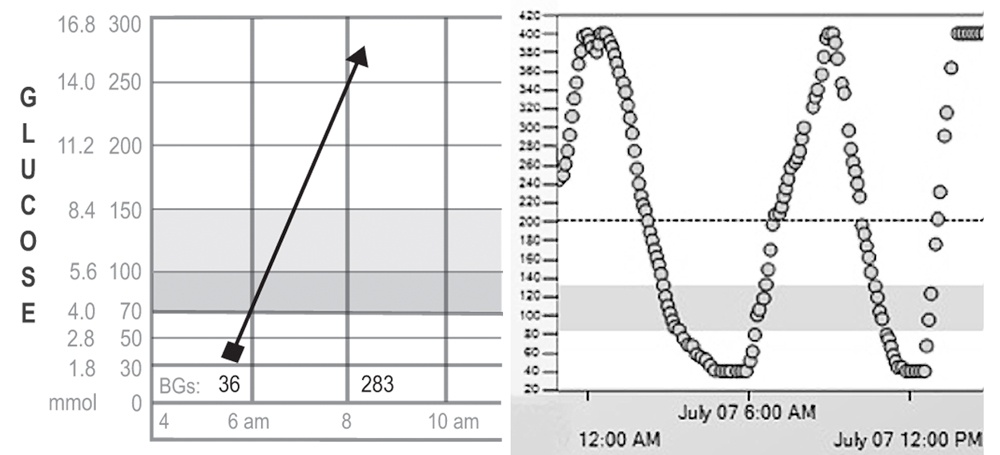

D. Overtreatment of Night Lows

- This pattern is easy to spot on a CGM because the glucose goes high following a low.

- Reduce excess insulin doses during the evening hours and at bedtime to prevent nighttime lows. Remember not to overtreat them when they do occur.

- Decrease the evening and night basal rates, and cover any excess bedtime IOB with carbs.

10. Highs after Over-Treating Lows (Rocketeer)

To eliminate lows to highs, simply stop over-treating lows with excess carbs. Use glucose tablets or fast-acting carbs at the very first sign of a low or as soon as an alert on your CGM sounds before excess stress hormones get released. Fast carbs take about 15 minutes to start to raise the glucose on a meter and about 20 minutes on a CGM, so don’t expect immediate results. Even in the panic of a low, it is harder to overdose on glucose tabs than it is on cookies, candy bars, or fruit juice. Avoid rebounds – get the Right Grams of Carb for Any Low Glucose.

Taking a bolus may seem strange when you are low, but if you consume too many carbs, a bolus is precisely what’s needed to prevent the high reading that will follow these excess carbs. Anytime a low glucose is over-treated, count the excess carbs, subtract any carbs needed to cover excess IOB, and give a carb bolus for the rest. The correct bolus will bring your glucose to your target 4 to 5 hours later without another low.

Don’t skip a bolus if you are low before a meal. Skipped boluses just make the next reading high and put you on a roller coaster. Instead, look back and fix what caused the low, check your CGM trend line, and consider a small reduction in the bolus dose.

Keep an eye on how many lows you are having. An excessive focus on high readings sometimes masks that many many high glucose readings originate from the overtreatment of lows. If readings go below 70 mg/dl (3.9 mmol/L) nearly every day, lower your TDD or a particular basal rate or CarbF to eliminate these frequent lows. You won’t see the forest (frequency of lows) until you stop looking at the trees (high readings that follow).

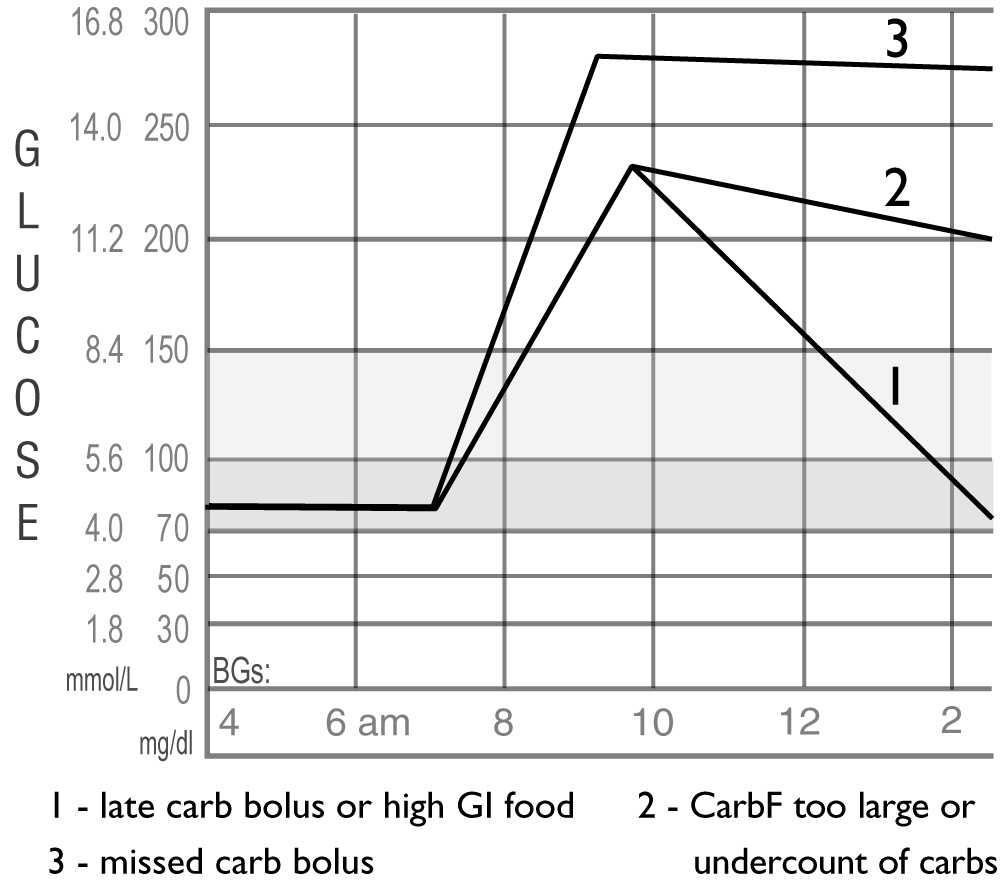

11. Post-Meal Spiking (Big Waves)

1. A Late Meal Bolus or High GI Food

- To fix this, bolus for the meal earlier. Insulin, even rapid-acting insulin, works much slower than most foods, especially high Glycemic Index foods. Give boluses 15 to 30 minutes before meals to correct this.

- Reduce the amount of high glycemic index food and select lower glycemic index foods, or add fiber like psyllium or Super Seed fiber to high GI foods.

- Another solution comes from the use of a Super Bolus or adding some low GI carbs or fiber to the meal.

- Remember: a CGM is a great tool to match the timing and size of your boluses with the foods you eat.

- Some medications help reduce post-meal spiking.

2. Carb Bolus Too Small or Carb Counting Needs Improvement

This line shows the glucose rise after a meal then falling, but not back to where it started.

Many factors can cause this, so zero in on what’s not working to improve your management skills.

Consider:

- A lower CarbF number.

- Carb boluses as a whole may not be large enough. They usually make up 36-45% of TDD, while keeping correction boluses below 10% of your TDD. Lowering your CarbF may accomplish this.

- Carb counts may not be accurate. Use an app, a book like the Calorie King Calorie, Fat, and Carbohydrate Counter, or a restaurant’s nutritional info when eating out.

- Improve portion size estimates. Weigh or measure foods for a while until you get the hang of it.

- Don’t snack between meals without blousing.

- Are you reducing your bolus amounts due to fear of hypoglycemia? You’re on a CGM, right? Remember, you don’t have to do that anymore! Trust your CGM to alert you to lows.

- To estimate how many units you should bolus when your glucose is still high 4 hours after a meal, refer to Table 12.9.

| 12.9 How Much Insulin Was Missed When a Glucose Is High 4-5 hrs After a Meal? | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||

| Your TDD (u/day) | Your Glucose 4-5 hours after Your Last Bolus [mg/dL (mmol/L] | ||||||

| 160 (8.9) |

200 (11.1) |

240 (13.3) |

280 (15.6) |

320 (17.8) |

360 (20) |

400 (22.2) |

|

|

20 u 30 u 40 u 50 u 60 u 70 u 80 u 100 u |

+0.4 u +0.6 u +0.8 u +1.0 u +1.3 u +1.5 u +1.7 u +2.1 u |

+0.8 u +1.3 u +1.7 u +2.1 u +2.5 u +2.9 u +3.4 u +4.2 u |

+1.3 u +1.9 u +2.5 u +3.2 u +3.8 u +4.4 u +5.1 u +6.3 u |

+1.7 u +2.5 u +3.4 u +4.2 u +5.1 u +5.9 u +6.7 u +8.4 u |

+2.1 u +3.2 u +4.2 u +5.3 u +6.3 u +7.4 u +8.4 u +10.5 u |

+2.5 u +3.8 u +5.1 u +6.3 u +7.6 u +8.8 u +10.1 u +12.6 u |

+2.9 u +4.4 u +5.9 u +7.4 u +8.8 u +10.3 u +11.8 u +14.7 u |

3. Missed Carb Bolus

This one’s easy to spot. Your graph goes up and stays up.

- Check your pump history to see if you forgot to bolus.

- If you neglected to bolus and remember within an hour of eating your meal, bolus for the missed carbs, but only a small portion of the usual correction bolus for the high glucose.

- If you forgot and it’s been more than 2 hours, take only a correction bolus because the carbs have been digested and are no longer raising your glucose.

Periodically check your basal/carb bolus balance.

Most adults and adolescents do best with about 55% (45-60%) of the TDD as basal insulin. The basal percentage is often lower than this in children prior to puberty and in lean older adults.

For frequent lows, lower your basal rates if your basal insulin makes up over 55-60% of avg. TDD, or raise your CarbF/ICR to get smaller boluses if carb boluses make up more than 45-50% of the TDD.

For frequent highs, raise your basal rates if your basal insulin makes up less than 45-50% of the average TDD, or lower your CarbF/ICR and ensure accurate carb counts if carb boluses make up less than 40-45% of TDD.

You have some awesome sources. Can you direct me to the literature or studies that you got this from?

Many thanks for the appreciation, Laticia!!!

New ideas and tools are constantly under development to improve pattern recognition, especially for today’s automated insulin delivery devices. The material on these pages comes from my decades of clinical experience with a focus on the development of better diabetes management tools.

Best regards,

John

Dr Walsh, your book and this site is a lig saver. I have just found it and will be telling all my sweet friends (punt intended). LOL

Thank you seems so insignificant. You are awesome!!!!

Hi John,

this is like a Rosetta Stone for me and my Insulin/Pump Management. I had been searching for such a resource for weeks and had only found partial or over-simplistic information even from some experienced looper. So in my eyes this is the first comprehensive overview on BG patterns and how to deal with them. Thank you so much for sharing these informations! You are really awesome!

Best regards,

Rainer

I have been T1D for 37+ years. I am living in a very rural area and don’t have the opportunity to get to an endocrinologist. I rely on my Primary care doctor who I have been seeing for years and he is great at helping me with my pump and my CGM. I have a background of family members that are also T1D so I grew up knowing what to do and so forth but this page has been awesome. I appreciate the graphs here because it puts things into perspective even though my numbers are very different. The ideas are the same. Thank you for what you provide here.