Insulin action time (how fast insulin starts working, when it peaks, and how long it lasts) is one of the most practical “missing pieces” for better day-to-day glucose control. Whether you use injections, a pump, or an AID system, timing insulin around meals and activity helps minimize highs, avoid lows, and maximize the benefits of your diabetes tools.

When people feel like their numbers are “random,” insulin timing is often the real reason. The good news: once you know your insulin’s action pattern, you can make smarter decisions about pre-bolusing, corrections, exercise, and preventing insulin stacking.

Searching for a specific answer? Jump to our Frequently Asked Questions for quick timing tips and common “what do I do now?” scenarios.

Direct answer: Match insulin timing to digestion and glucose changes by using these 4 rules:

- Pre-bolus when safe: most rapid insulins work best when taken 10–20 minutes before eating (shorter if you’re near 90 mg/dL (5.0 mmol/L) or trending down).

- Don’t “double-correct” too soon: rapid insulin often keeps working for 4.5–6 hours, so a second correction too early can cause a low later.

- Respect the peak window: lows are most likely near an insulin’s peak (for rapid insulin, often 2–5 hours after a bolus).

- Use CGM + pattern tracking: trends help you see whether the insulin is still rising, peaking, or wearing off.

Why does insulin timing matter?

A good way to improve glucose levels is to track your highs and lows and understand how your insulin’s onset, peak, and duration relate to them. Most glucose fluctuations can be explained by insulin timing mismatches—insulin starts later than expected, food hits faster than insulin, or insulin is still active when you assume it’s “done.”

Once you understand timing, you can:

- Reduce post-meal spikes (especially above 180 mg/dL (10.0 mmol/L))

- Prevent late lows (especially below 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L))

- Avoid insulin stacking (taking more insulin while the previous dose is still working)

- Make pumps and AID systems work more smoothly (less “algorithm lag”)

What do onset, peak, and duration mean?

- Onset: how long it takes insulin to start lowering glucose after you take it.

- Peak: when insulin is working its strongest (this is often when lows are most likely if carbs are not available).

- Duration: how long insulin keeps lowering glucose before it fully wears off.

💡 Important: Action times are averages. They can vary day to day based on dose size, infusion site, temperature, activity, stress, illness, and how quickly food digests.

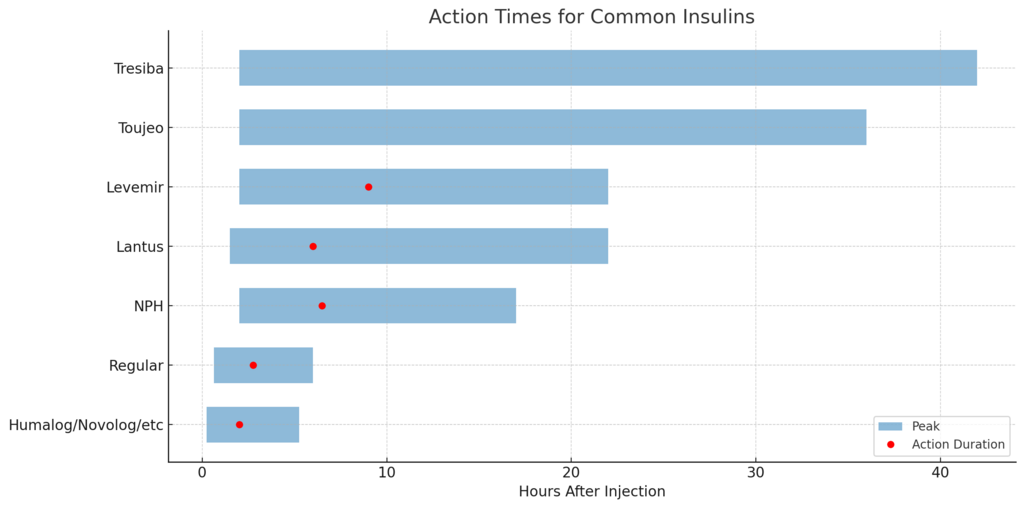

What are the action times for common insulins?

| Insulin Type | Starts (Onset) | Peaks | Ends (Duration) | Low Most Likely At | Primary Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Humalog, Novolog, Apidra, Fiasp, Admelog, Lyumjev | 10–20 min | 1.5–2.5 h | 4.5–6 h | 2–5 h | Meals & high blood sugar corrections |

| Regular | 30–45 min | 2–3.5 h | 5–7 h | 3–7 h | Meals, delayed digestion, or use with Symlin |

| NPH | 1–3 h | 4–9 h | 14–20 h | 4–12 h | Intermediate background or nighttime insulin |

| Lantus | 1–2 h | ~6 h | 18–26 h | 6–10 h | Long-acting basal insulin |

| Levemir | 1–3 h | 8–10 h | 18–26 h | 8–14 h | Long-acting basal insulin |

| Toujeo | ~2 h | None | ~36 h | Varies | Flat, extended basal insulin |

| Tresiba | ~2 h | None | ~42 h | Varies | Ultra-flat, ultra-long basal insulin |

How fast do rapid-acting insulins work?

Rapid-Acting Insulin Action Time

Humalog, Novolog, Apidra, Fiasp, Lyumjev, and Admelog are all rapid-acting insulins used to cover meals and correct high blood glucose levels. These insulins:

- Start working in 10–20 minutes

- Peak at 1.5–2.5 hours

- Last for 5+ hours

💡 Although their action is labeled as 3–5 hours, true effects often last longer, especially in sensitive individuals.

How to use this at meals: Because digestion often peaks before insulin does, many people do best by bolusing before meals (when safe) and choosing lower-glycemic foods when possible. If you frequently spike above 180 mg/dL (10.0 mmol/L) at 60–90 minutes after eating, it’s often a sign that insulin started too late, the carbs hit faster than expected, or the dose timing didn’t match the meal.

When does Regular insulin work best?

Regular insulin has a slower onset and peak, making it better suited for:

- Delayed digestion

- Use with Symlin or gastroparesis

- Cost-conscious users (available at low prices)

It does carry a slightly higher risk of nighttime hypoglycemia due to its longer duration and overlap between doses. If you’re using Regular insulin and you’ve had late lows (for example, dipping under 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L) overnight), discuss timing, dose size, and carb planning with your clinician.

Do long-acting basal insulins really last 24 hours?

Long-Acting Basal Insulin Action Time

Though often thought of as “24-hour insulins,” Lantus and Levemir frequently provide only 18–26 hours of action. This may cause:

- Peaking effects at 6–10 hours

- Gaps in coverage before the next dose

- Stacking or overlapping if doses aren’t consistently timed

Splitting the daily dose into morning and evening halves often improves coverage and stability.

How to recognize a basal “gap”: If glucose rises steadily at the same time every day (without food), it can point to a basal dose that’s wearing off early. If glucose drops at roughly the same time each day, it can suggest too much basal or a basal peak that’s hitting you.

What’s different about ultra-long-acting basal insulins?

Toujeo (U-300 glargine) and Tresiba (degludec) are designed for minimal peaks and very long duration — up to 42 hours. They provide:

- Flatter profiles

- More predictable action

- Less risk of coverage gaps

Practical timing tip: Because they are so long-acting, dose changes can take longer to “show up” fully. It can help to make changes cautiously and then give your body time to settle, especially if you’re prone to lows.

Why is NPH insulin still relevant?

Though older, NPH has a steeper peak and shorter duration that can be helpful for:

- Addressing the dawn phenomenon

- Combining with Lantus or Levemir

- Lower-cost alternatives to modern basal insulins

A bedtime dose of NPH may reduce early morning glucose rises, especially in people with Type 2 diabetes or adolescents with hormone-driven dawn spikes.

Why does timing matter even more for insulin pump and AID users?

If you’re using an insulin pump or automated insulin delivery (AID) system, all insulin delivered is rapid-acting. That makes timing even more important.

Pumps only use rapid-acting insulin

Pumps deliver rapid insulins like Lispro, Aspart, and Glulisine in two ways:

- Basal delivery: tiny pulses every few minutes

- Boluses: for food or high glucose

Since pumps do not use long-acting insulin, consistent absorption of rapid-acting insulin is essential.

Why pre-bolusing is crucial

Because rapid insulin is still slower than digestion, pump users often benefit from pre-bolusing 10–20 minutes before meals. This helps:

- Match the insulin peak to the glucose rise

- Prevent post-meal spikes

- Improve overall time-in-range

Safety nuance: If you are near 90 mg/dL (5.0 mmol/L) or trending down, a full 20-minute pre-bolus may be too aggressive. In that situation, a shorter pre-bolus (or even dosing at the first bite) may be safer.

How do infusion sites and activity change absorption speed?

- Abdomen = fastest absorption

- Thigh or arm = slower, especially if sedentary

- Exercise = speeds up insulin action, which may lead to lows

Practical example: If you bolus in an area that absorbs slowly and then begin activity that speeds absorption, insulin action can “catch up” suddenly later—raising the risk of a delayed low under 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L).

Do AID systems still depend on timing?

AID systems, such as Tandem Control-IQ, Omnipod 5, and Medtronic 780G, adjust insulin based on CGM data. But they’re still limited by:

- How fast insulin starts working

- How quickly glucose rises from food

- Site absorption variability

Slow infusion site absorption can lead to post-meal highs or algorithm lag, reducing AID effectiveness.

How do I avoid insulin stacking when correcting high blood sugar?

Insulin stacking happens when you take a correction dose while your earlier insulin is still active. Because rapid insulin can last 4.5–6 hours, a common “trap” is correcting again at 90–120 minutes when you’re still above 180 mg/dL (10.0 mmol/L), even though the first dose hasn’t peaked yet.

- Use your IOB (insulin on board): pumps and many apps estimate how much insulin is still active.

- Check the trend: if glucose is falling steadily, a second correction may backfire later.

- Consider the cause: slow digestion, high-fat meals, missed bolus timing, or a weak infusion site can all delay the “visible” impact.

Best habit: When you see a stubborn high, ask, “Is insulin still working?” before adding more. This single question prevents many late lows.

What’s the big takeaway for better daily control?

Understanding insulin timing is key, whether you’re on injections or a pump. When you know:

- When insulin starts working

- When it peaks

- How long does it lasts

…you can match insulin delivery to your body’s needs—and take control of your blood sugars with fewer surprises.

Helpful Resources & Research

- American Diabetes Association: Insulin Basics

- CDC: Using Insulin to Treat Diabetes

- Endocrine Society: Insulin Therapy Overview

- NIDDK: Insulin and Blood Glucose Management

- Cleveland Clinic: Guide to Insulin

Frequently Asked Questions

What is insulin action time?

Insulin action time is how long insulin takes to start working (onset), when it works strongest (peak), and how long it keeps lowering glucose (duration). Knowing this helps you time meals, corrections, and activity so you avoid spikes and “sugar crashes.”

How long does rapid-acting insulin really last?

Even if a label says 3–5 hours, many people feel rapid insulin effects for about 4.5–6 hours (sometimes longer). That’s why late lows can happen 2–5 hours after a bolus and why double-corrections can backfire.

When should I pre-bolus for meals?

Many people do best pre-bolusing 10–20 minutes before eating. If you’re near 90 mg/dL (5.0 mmol/L) or trending down, a shorter pre-bolus (or dosing at the first bite) is often safer.

Why do I spike after meals even when I bolus?

Common causes include bolusing too late, eating fast-digesting carbs, or slow insulin absorption (site issues). Digestion often rises faster than rapid insulin, so timing and meal type matter.

What does “low most likely at 2–5 hours” mean for rapid insulin?

It means that even if you feel fine at 1 hour, your risk of dropping under 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L) is often higher later—especially if you exercised, ate less than expected, or corrected a high.

How do I avoid insulin stacking when correcting a high?

Check insulin on board (IOB), watch your CGM trend, and remember rapid insulin may still be active for 4.5–6 hours. If glucose is already falling, adding more insulin can cause a late low.

Do long-acting basal insulins always last 24 hours?

Not always. Lantus and Levemir can act roughly 18–26 hours in many people, which can cause coverage gaps or peaks. If you see consistent timing patterns (daily rises or drops without food), your basal timing or split dosing may need review with your clinician.

Why does exercise change insulin action?

Exercise can speed insulin absorption and make you more insulin-sensitive. A bolus that felt “normal” on a rest day can cause a low during or after activity, especially if you were near 90 mg/dL (5.0 mmol/L) to start.

Why do AID systems still need pre-bolusing?

AID systems react to CGM data, but insulin still takes time to work and food can raise glucose quickly. Pre-bolusing helps reduce “algorithm lag” and lowers the size of post-meal spikes.

What’s the simplest timing habit that improves control fastest?

Track your highs and lows alongside the time you bolused and what you ate. Then ask, “Was insulin still rising, peaking, or wearing off?” That one question often explains the pattern and shows the next best adjustment.

Last Updated on January 15, 2026