GLP-1 agonists are medications for diabetes that imitate a natural gut hormone to help regulate your blood sugar after meals. To maintain stable blood sugar levels, your body relies on insulin from the pancreas to lower blood sugar and a nearby hormone called glucagon to raise it when needed, during the night and during physical activity. When beta cells are lost in type 1 diabetes or gradually become inactive in type 2 diabetes, the two hormones they produce—insulin and amylin—are also lost. Insulin is the most critical because a person can die quickly without it. However, amylin from beta cells is especially important after meals; it signals nearby alpha cells to reduce glucagon release. Without amylin, inappropriate glucagon release after eating can happen, which then increases your blood sugar even more.

GLP-1 agonists are medications for diabetes that imitate a natural gut hormone to help regulate your blood sugar after meals. To maintain stable blood sugar levels, your body relies on insulin from the pancreas to lower blood sugar and a nearby hormone called glucagon to raise it when needed, during the night and during physical activity. When beta cells are lost in type 1 diabetes or gradually become inactive in type 2 diabetes, the two hormones they produce—insulin and amylin—are also lost. Insulin is the most critical because a person can die quickly without it. However, amylin from beta cells is especially important after meals; it signals nearby alpha cells to reduce glucagon release. Without amylin, inappropriate glucagon release after eating can happen, which then increases your blood sugar even more.

Looking for a specific answer? Jump to our Frequently Asked Questions for quick info about GLP-1 medications.

What Are GLP-1 Agonists?

| Medication | Dosing Frequency | Avg. A1c Reduction* |

|---|---|---|

| Ozempic (semaglutide) | Weekly injection | 1.5-2.0% |

| Trulicity (dulaglutide) | Weekly injection | 1.5-1.8% |

| Rybelsus (semaglutide) | Daily pill | 1.0-1.4% |

| Mounjaro (tirzepatide)** | Weekly injection | 2.0-2.4% |

*A1c measures your average blood sugar over the past 2-3 months. Each 1% reduction in A1c roughly corresponds to an average blood sugar decrease of about 25-30 mg/dL (1.4-1.7 mmol/L), though this varies by individual. **Tirzepatide is a dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist, not a GLP-1-only medication

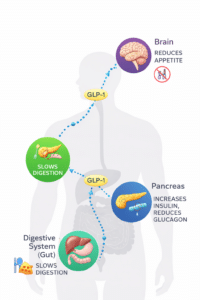

Amylin is not the only substance that helps control glucagon. Some gut hormones also lower glucagon levels. Although the name can be a bit misleading, Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 agonists (GLP-1s) are diabetes drugs that mimic the natural gut hormone GLP-1, which, unlike glucagon, decreases your blood sugar and reduces glucagon, especially after meals.

GLP-1 and glucagon both originate from the same parent compound called proglucagon, but they have very different effects. GLP-1 agonists (which means they “mimic” natural GLP-1) lower both your blood sugar and glucagon levels while slowing digestion, increasing insulin secretion, and reducing appetite. These medications are vital in treating type 2 diabetes by lowering after-meal blood sugar, supporting weight loss, and helping to preserve insulin-producing cell function over time.

GLP-1s are a class of diabetes medications that imitate the natural hormone glucagon-like peptide-1. These drugs can lower blood sugar after meals, aid in weight loss, and may help preserve beta-cell function in type 2 diabetes. GLP-1 agonists like liraglutide (Victoza), lixisenatide (Adlyxin), dulaglutide (Trulicity), and semaglutide (Ozempic, Rybelsus) are commonly prescribed and continue to demonstrate benefits beyond just controlling blood sugar, including improvements in heart and metabolic health for some drugs. GLP-1–based therapy is also mentioned in the 2026 ADA Standards of Care as part of risk-based treatment options for many adults with type 2 diabetes.

In 2026, ADA/EASD guidance continues to emphasize GLP-1–based therapy for many people with type 2 diabetes, especially when weight control is important, or there’s a risk of heart or kidney problems. Some GLP-1 options have also demonstrated cardiovascular benefits, and newer “incretin-based” medications include dual-agonists (such as GIP/GLP-1) that work similarly but are not exactly the same drug class.

What Are Incretins and the “Incretin Effect”?

As you know, insulin, whether produced naturally by beta cells or given externally, lowers your blood sugar levels. In 1902, twenty years before insulin was discovered, other compounds from the gut, called incretins, were found to reduce blood sugar and affect other biological processes. This wasn’t surprising since the gut was the first organ to develop, well before the pancreas, liver, or brain. Researchers believed that the gut could directly signal to your pancreas.

Later, in 1930, the term “incretin” was introduced to describe the increased glucose-lowering effect observed when a gut extract was fed to dogs. Then, in the 1960s, researchers discovered that almost twice as much insulin was released when glucose was infused directly into the gut instead of into the bloodstream via an IV. This sparked renewed interest in identifying compounds produced by the gut that could help lower your blood sugar levels.

The first incretin approved by the FDA in May 2005 was Byetta (exenatide). This GLP-1 agonist lasts longer in the body but has the same effects as natural GLP-1. Its origin was somewhat unusual, as it was derived from a compound found in the saliva of the Gila monster, a large lizard native to the southwestern US. Gila monsters eat only about 5 to 10 times a year, so researchers suspected they could provide interesting incretins to study. One incretin modified from Gila monster saliva became Byetta. In addition to lowering your blood sugar levels, research showed that people taking Byetta eat about 20% less and often lose weight. However, Byetta and its extended-release version Bydureon BCise were discontinued in 2024.

After a meal, incretin hormones are released into your bloodstream from the gut. Glucagon-like peptide-1 is an incretin hormone known for its ability to lower your blood sugar levels, especially after eating and during fasting, by acting on organs like your pancreas and brain.

How Does GLP-1 Function in Various Organs?

In Your Gut

GLP-1 slows intestinal absorption, helping injected insulin’s delayed response better match digestion and improve your after-meal readings. If you’re using insulin pump therapy, this slower digestion can make it easier to synchronize your insulin delivery with carbohydrate absorption. This benefit applies to both type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

In Your Pancreas (Insulin Production)

GLP-1 promotes insulin release from beta cells by supporting their growth and increasing their numbers. This often restores first-phase insulin secretion and production, helping to prevent blood sugar spikes after meals. This protective effect is mainly advantageous for type 2 diabetes, where beta cells are still present but not functioning well.

In Your Pancreas (Glucagon Control)

GLP-1 decreases the inappropriate and excessive release of glucagon after meals. This also helps lower your blood sugar levels following meals. This benefit applies to both type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

In Your Brain

GLP-1 boosts dopamine, helping with weight management and possibly treating certain addictive behaviors. It also blocks an appetite receptor in the hypothalamus, reducing hunger and promoting feelings of fullness in people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

Why Can’t Natural GLP-1 Be Used as a Medication?

GLP-1 itself cannot be used as a medication because it is broken down in less than 2 minutes by an enzyme called DPP-4 found throughout your body. To address this, GLP-1 agonists have been developed to mimic GLP-1 without being broken down as quickly. These medications can last hours or even days in your bloodstream, providing sustained blood sugar control.

What 2026 GLP-1 Options Are Available, and How Are They Given?

Most GLP-1 receptor agonists are given as a small injection under your skin, typically once a week. There is also an oral option called oral semaglutide (Rybelsus) for type 2 diabetes. Some older GLP-1 drugs have been discontinued or removed from the market, but the drug class remains very active.

Related “incretin-based” medicines you might hear about include tirzepatide (Mounjaro for type 2 diabetes, and Zepbound for chronic weight management), a dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist given as a once-weekly injection. It is not a “GLP-1-only” agonist, but it is often discussed alongside GLP-1 medications because many of the benefits and side effects overlap.

Long-acting insulin combined with GLP-1 injections (once daily): Some people with type 2 diabetes use a single daily shot that includes a basal insulin and a GLP-1 medication, such as insulin glargine/lixisenatide (SOLIQUA 100/33) or insulin degludec/liraglutide (XULTOPHY 100/3.6). These can make treatment easier for those who need help controlling blood sugar levels both fasting and after meals.

How Effective Are GLP-1 Agonists for Type 2 Diabetes?

GLP-1 agonists lower blood sugar levels and improve glycemic control in people with type 2 diabetes, often delaying the need to start insulin. They have a low risk of sugar crashes (hypoglycemia), support weight loss, and enhance beta-cell function, lipid levels, and blood pressure. Used alone or with insulin, they significantly improve after-meal blood sugar levels for most users. However, like other diabetes medications, they are not as effective as insulin at lowering blood sugar.

Starting early with a GLP-1 for type 2 diabetes seems to be essential. GLP-1s protect your insulin-producing beta cells, help keep their function intact, and support blood sugar management, often for years. A 2017 report in The Lancet showed that people with pre-diabetes and obesity treated with liraglutide for 3 years had only a third develop into type 2 diabetes compared to those not treated. GLP-1s can greatly slow the progression of type 2 diabetes when used early, before beta-cell mass and function are lost, helping to preserve or potentially restore these cells. However, GLP-1 agonists are unlikely to protect beta cells in type 1 diabetes, even though their other effects can be quite helpful.

Insulin production in your pancreas is significantly reduced by the time type 2 diabetes is diagnosed, so any medication that increases insulin production and lowers blood sugar levels is very helpful. Unlike a glitazone medication like Actos (pioglitazone), which improves insulin sensitivity, GLP-1 agonists do not mainly work by directly “unlocking” insulin resistance the way a sensitizer does—although weight loss from GLP-1 therapy can indirectly improve insulin sensitivity. Because of their different protective actions, these two drug classes may have additive effects that help preserve beta cells.

Both GLP-1 agonists and Actos slow the decline of insulin production, which is a key reason for rising blood sugar levels over time, leading many with type 2 diabetes to start insulin therapy. In his 2008 Banting Lecture to the American Diabetes Association, Dr. Ralph DeFronzo, a diabetes expert and researcher at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio, advised that these two medication classes be considered first when treating type 2 diabetes because they help preserve beta-cell function. He also suggested they might be used in people with prediabetes because of their ability to protect beta cells. This approach simplifies blood sugar control and can delay or lessen the need for insulin.

When Should You Consider a GLP-1 Agonist?

Your doctor may recommend a GLP-1 agonist if you:

- Have type 2 diabetes and need better blood sugar control after meals

- Need to lose weight to improve your diabetes management

- Have cardiovascular disease or are at high risk for heart problems

- Have chronic kidney disease (certain GLP-1s have kidney-protective benefits)

- Haven’t reached your blood sugar targets with metformin alone

- Want to delay or avoid starting insulin therapy

Do GLP-1 Agonists Help with Type 1 or Type 1.5 Diabetes?

Unfortunately, GLP-1 agonists do not maintain insulin production in type 1 or type 1.5 diabetes. In these cases, diabetes occurs because the immune system attacks and gradually destroys the beta cells responsible for producing insulin. GLP-1 agonists cannot stop this process.

Although not yet approved for type 1 diabetes, GLP-1 agonists have been tested in multiple trials involving people with the condition. The researchers observed a non-significant A1c reduction of 0.6%, compared to 0.2% in controls, along with a weight loss of 14.1 pounds (6.4 kilograms). Nausea was the most common side effect. The authors concluded: “The use of GLP-1 agonists should be considered in T1DM patients who are overweight or obese and not at glycemic goals despite aggressive insulin therapy.”

After conducting clinical trials with a GLP-1 agonist, Novo Nordisk decided not to pursue FDA approval for treating type 1 diabetes. They were disappointed by a non-significant 0.5% reduction in A1c among patients taking the drug, compared to a 0.3% reduction in the placebo group, all of whom had poorly controlled A1c levels above 8%. The trial showed no decrease in sugar crashes but did lead to an average weight loss of 10 pounds.

What Emerging Uses for GLP-1s Are Being Studied?

Ongoing research highlights the significant clinical potential of incretin-based therapies, especially in emerging areas such as central nervous system disorders, substance use, and post-transplant care. GLP-1s show promise in reducing nerve inflammation and cell death while supporting nerve health. Early trials suggest possible benefits for Parkinson’s disease. Results for Alzheimer’s disease have been mixed. GLP-1s also seem to decrease substance use disorders by affecting dopamine pathways, particularly in alcohol use disorder. Outcomes for nicotine and cocaine addiction are less definitive.

Observational data also indicate that GLP-1 receptor agonists may improve outcomes following kidney and liver transplants. For liver transplants, benefits include enhanced organ function, reduced liver fat, and less scarring. In kidney transplants, a slower decline in glomerular filtration rate, which measures kidney function, has been observed compared to other diabetes treatments.

How Do You Safely Begin and Titrate a GLP-1 Agonist?

GLP-1 agonists come in pens that enable gradual dose increases. Accurate dosing is essential. Clinicians usually start GLP-1s at a low dose to avoid nausea and other side effects, then slowly increase the dose every 1 to 4 weeks based on your tolerance and blood sugar response.

Another good way to determine the right dose is to check several pre-meal and 2-hour post-meal blood sugar levels, or to use a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) for breakfast and dinner over a few days. If you’re using a CGM, you can monitor your time-in-range and see how well the medication controls your after-meal spikes. This data-driven approach helps you and your healthcare provider find the best dose.

For context, the ADA’s typical blood sugar targets for many nonpregnant adults include a pre-meal level of 80–130 mg/dL (4.4–7.2 mmol/L) and a peak after-meal level of less than 180 mg/dL (<10.0 mmol/L). However, your individual targets may vary depending on your age, duration of diabetes, and other health factors.

Example: If your pre-meal reading is typically 145 mg/dL (8.0 mmol/L) and your 2-hour after-meal reading is 210 mg/dL (11.7 mmol/L), these are above target. A properly dosed GLP-1 might bring these down to 115 mg/dL (6.4 mmol/L) pre-meal and 160 mg/dL (8.9 mmol/L) after meals within 8-12 weeks.

GLP-1 agonists taken once a week typically cause fewer side effects, but no one wants to start with a week of nausea or vomiting! Again, with these medications, begin with the lowest dose, increase gradually, and give your body time to adjust before progressing to the next level.

Oral semaglutide (Rybelsus) timing tip: This is a pill, but the “how” matters. It is taken first thing in the morning on an empty stomach, with a small amount of water (no more than 4 ounces). Wait at least 30 minutes before eating, drinking, or taking other medications to ensure proper absorption.

What Side Effects Should You Watch For and When Should You Contact Your Doctor?

Occasionally, and for unknown reasons, a person might be unable to tolerate even a small dose of a GLP-1 agonist, requiring an alternative approach. The most common side effects include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation. These usually improve over time as your body adjusts to the medication.

Call your doctor and stop the medication immediately if you experience unusual abdominal pain or intestinal issues. Although there was initial concern about pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas), large reviews have not shown a clear increased risk across the GLP-1 class. However, severe or persistent abdominal pain should always be evaluated promptly.

Labeling update (2026): The FDA recently removed suicidal behavior and ideation language from the labeling of certain GLP-1 medicines used for chronic weight management, following a comprehensive safety review that found no evidence of increased risk. This update applies to medications like Wegovy (semaglutide) and Zepbound (tirzepatide) when used for weight management.

What Are the Benefits of GLP-1 Agonists?

| Benefit | How It Helps |

|---|---|

| Less blood sugar variability | Fewer highs and lows throughout the day |

| Lower after-meal levels | Reduces spikes while slightly lowering fasting levels |

| Weight loss support | Often helps with 5-15% body weight reduction |

| Low sugar crash risk | Doesn’t cause lows unless combined with insulin or sulfonylureas |

| Once-weekly dosing | More convenient than daily pills for some people |

Additional advantages include:

- May improve and preserve beta-cell health and delay or reduce the need for injected insulin in type 2 diabetes

- Generally safe for people with liver or heart issues (some formulations show cardiovascular benefits)

- Can be used with insulin pump therapy or multiple daily injections

- Works well when combined with continuous glucose monitoring to track effectiveness

What Are the Disadvantages of GLP-1 Agonists?

| Limitation | What This Means |

|---|---|

| Injection required | Most need weekly shots (except oral semaglutide) |

| Not FDA-approved for type 1 | Research shows some benefits, but not officially approved |

| Nausea common initially | Usually goes away, but may require dose adjustment |

| Not for everyone | Avoid if you have GI issues or moderate-to-severe kidney disease |

Responses to GLP-1 agonists differ greatly between individuals. Some people experience significant blood sugar improvement and weight loss, while others may see more modest benefits or struggle with side effects. Working closely with your healthcare team to find the right medication and dose is essential.

Helpful Resources & Research

- ADA Standards of Care 2026: Pharmacologic Approaches to Glycemic Treatment (Section 9)

- ADA Standards of Care 2026: Chronic Kidney Disease and Risk Management (Section 11)

- ADA Standards of Care 2026 (PMC): Glycemic goals table including 80–130 mg/dL (4.4–7.2 mmol/L) and <180 mg/dL (<10.0 mmol/L)

- FDA (Jan 13, 2026): Removal request for suicidality language on certain GLP-1 weight-management labels

- Rybelsus (oral semaglutide) FDA label (PDF)

- Ozempic (semaglutide injection) FDA label (PDF)

- Trulicity (dulaglutide) prescribing information (PDF)

- Adlyxin (lixisenatide) FDA label (PDF)

- FDA: Zepbound (tirzepatide) approval for chronic weight management

- Discontinuation notice: Byetta and Bydureon BCise (exenatide) in 2024

- Fehse F, et al. (2005) Exenatide augments first- and second-phase insulin secretion (PubMed)

- Kolterman OG, et al. (2005) Exenatide pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics/safety (PubMed)

- Three years of liraglutide vs placebo for type 2 diabetes risk reduction and weight management (The Lancet)

- Janzen KM, Steuber TD, Nisly SA. GLP-1 agonists in type 1 diabetes mellitus (PubMed)

- Storgaard H, et al. (2017) GLP-1 receptor agonists and pancreatitis risk (PubMed)

- Nauck MA, Friedrich N. (2013) Do GLP-1–based therapies increase cancer risk? (PubMed)

- Klonoff DC, et al. (2008) Exenatide effects over ≥3 years (PubMed)

Frequently Asked Questions

What are GLP-1 agonists?

GLP-1 agonists are medicines that mimic a gut hormone that helps your body handle food more effectively. They can lower your blood sugar after meals, reduce appetite, and often help with weight loss. Most are given as a weekly injection, though an oral pill (Rybelsus) is also available for type 2 diabetes.

Do GLP-1 agonists cause low blood sugar (sugar crashes)?

They do not cause lows on their own. The risk increases if you also take insulin or a sulfonylurea (such as glipizide), because those drugs can work together in ways that drop your blood sugar too much. Your doctor may reduce doses of those medications when starting a GLP-1.

Are GLP-1 medicines shots or pills?

Most are small injections given under your skin, usually weekly. An oral option for type 2 diabetes is also available: oral semaglutide (Rybelsus), which is taken as a daily pill on an empty stomach.

How quickly will I see the benefits of GLP-1?

Many people notice changes in appetite within a few days to a couple of weeks. Your blood sugar levels—especially after meals—often improve as the dose is gradually increased over several weeks. Full benefits typically develop over 8-12 weeks as your body adjusts to the medication.

What’s the best way to reduce nausea when starting a GLP-1?

Start with a low dose and increase gradually. Don’t “push through” worsening nausea—pause longer at the current dose or step back. Smaller meals, less greasy food, and slower eating also help. If nausea persists, talk to your doctor about adjusting your dose.

What blood sugar numbers should I check to see if it’s working?

A practical approach is to track pre-meal and 2-hour after-meal readings for a few days before and after dose adjustments. Typical ADA targets for many adults are 80–130 mg/dL (4.4–7.2 mmol/L) before meals and <180 mg/dL (<10.0 mmol/L) after meals, but your targets may differ.

Can people with type 1 diabetes use GLP-1 agonists?

They are not FDA-approved for type 1 diabetes. Some studies show weight loss and small A1c improvements in certain people, often those with overweight or obesity, but nausea and tolerability are common issues. Talk to your doctor if you’re interested in trying them.

Are GLP-1 agonists safe for your pancreas?

Early concerns about pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas) led to close monitoring. Overall, large reviews have not shown a clear increased risk across the class, but you should call your doctor right away if you experience severe or unusual abdominal pain.

Do GLP-1 agonists help heart health?

Some GLP-1 medicines have shown cardiovascular benefits and are prioritized for many people with type 2 diabetes who have established heart disease or high cardiovascular risk, according to ADA Standards of Care. Ask your doctor if you’re a candidate for one of these medications.

What’s the difference between GLP-1 and tirzepatide (Mounjaro or Zepbound)?

GLP-1 agonists target the GLP-1 receptor only. Tirzepatide targets both GLP-1 and another incretin receptor called GIP. It’s given weekly by injection and is often compared to GLP-1s because the effects (and side effects) overlap, but it tends to have stronger A1c reduction and weight loss effects.

Last Updated on February 12, 2026