See also: Humalog & Heat and User’s Reports

People often think that “rapid” insulins are faster than they are. For example, a person may feel perfectly healthy at 80 mg/dl (4.4 mmol), take a bolus of rapid insulin for a meal, and a few minutes later begin to shake, sweat, and have trouble thinking. The timing of these symptoms might give the impression this rapid insulin acts very quickly. However, the rapid insulin just given is likely not responsible for these symptoms. More likely, another dose given earlier may have caused the low glucose. A drop of only a few mg/dl causes a person to go from feeling normal to feeling low. Unrecognized insulin stacking is frequent. People often mistakenly blame the meal dose just given for low glucose caused by an insulin dose given 4 or 5 hours earlier in the day.

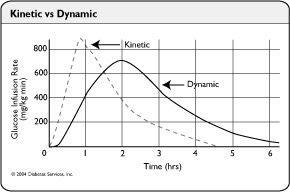

Kinetics Versus Dynamics with Insulin

The kinetics of insulin shows when an insulin dose appears in the bloodstream. Insulin dynamics (aka pharmacodynamics) show how long insulin lowers the glucose. After an injection or bolus, peak Humalog and Novolog insulin levels occur about 50 minutes later in the bloodstream. The dashed line on the left within the graphic shows kinetics. However, how insulin impacts your glucose is not nearly this quick. The longer solid line for dynamics to the right shows how long when the insulins lower the glucose. A maximum reduction in glucose occurs over 2 hours after the dose and continues for another 5 hours.

Another situation also contributes to many the impression that rapid insulin is rapid. This occurs when a carb or correction bolus is given, and low glucose begins only an hour later. Here, rapid insulin is an unlikely cause of the low glucose. Rather, the rapid drop in glucose originates from a carb or correction bolus that was too large or from unanticipated activity.

For instance, if enough Novolog is taken to cover 100 grams of carbohydrates, but only 50 grams are eaten, the excess insulin makes the blood glucose quickly. The lack of carbs might give a false impression that insulin acts quickly. Another contributor, insulin stacking, occurs when one bolus overlaps with another given within the last 5 hours. An excess in basal or long-acting insulins can also contribute to stacking.

When low glucose occurs less than 3 hours after a meal or correction dose is given, consider its cause carefully. There may be an error in carb counting, an overlap of two or more boluses, an excessive basal insulin dose, excess physical activity, a low glycemic index carbohydrate, or another factor such as delayed gastric emptying from gastroparesis that is responsible. Remember to note a reason for all unexpected lows and highs in your record book.

For additional information on Humalog and intensive management, carbohydrate counting, glycemic index, proper insulin doses, or exercise, get Pumping Insulin by John and Ruth, or Using Insulin by John, Ruth, and C Varma MD, T Bailey MD.