By John Walsh, PA, CDE and Ruth Roberts, MA

Authors of Pumping Insulin and Using Insulin

What is DIA?

Duration of insulin action (DIA) or insulin action time measures how long a bolus or injection of rapid insulin lowers your glucose after the bolus is given. Too often, insulin users give a bolus or dose and don’t consider how this dose will affect their glucose over the next few hours. If their glucose is high a couple of hours later, not realizing they still have active insulin on board, they may take more insulin and end up with a low reading. Bolus calculators help prevent this when the DIA is set correctly.

Research studies done 15 years ago accurately measured DIA (referred to as pharmacodynamics) for use in pumps or the new bolus calculators (BC) now becoming available in glucose meters. The results of DIA research studies have never been widely distributed, so people often use an inappropriate DIA setting, often one that is too short. Because the DIA has such an impact on control, always select the DIA time from research study results or from direct testing (see below). Depending on the way the DIA is calculated in your bolus calculator, set the DIA between 4.5 and 6 hours (See specifics below.).

It is especially important not to set the DIA time too short because this causes other pump settings to be thrown off, does not solve the real causes for poor control, and can be dangerous, as detailed below. Although a quick way to increase bolus insulin, shortening the DIA creates more problems than it is worth.

Insulin Stacking

An accurate DIA setting is needed to calculate residual bolus insulin activity or bolus on board (BOB) in order to avoid excessive insulin stacking. Stacking is common. Once the first bolus of the day is given, insulin stacking occurs whenever another bolus is given within the next 5 or 6 hours. Sixty-five percent of pump boluses are given within 4.5 hours of the last bolus,1 and today’s rapid insulins remain active longer than 4.5 hours.2,3,4,5 Because of this, if BOB is not accurately tracked, the risk of hypoglycemia is great. In 10.8% of boluses, the BOB exceeds the correction bolus needed to lower the current glucose to target. In this situation, carb intake would normally be needed.5

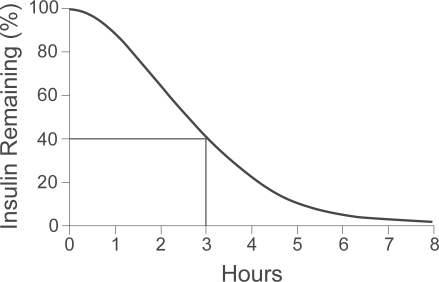

Once a bolus or injection of rapid insulins like Humalog, Novolog, or Apidra is given, its impact on the glucose can be seen over the next 5.5 to 6 hours. The little effect is seen in the first 15 to 20 minutes, about half its activity is gone at just over 2 hours, and the other half of its activity gradually decreases over the next 4 hours, giving a total DIA of about 6 hours. One crossover study comparing Humalog (lispro) and Novolog (aspart) in 7 people with Type 1 diabetes at Temple University found that both insulins lowered glucose levels between 5 and 6 hours (See Figure 1).6 In a study by Mudaliar and colleagues of 20 non-diabetic subjects, 40% of the glucose-lowering effect of Novolog (aspart) remained at 3 hours after an injection (See Fig. 2).2 If someone sets their DIA to 3 hours, about 40% of each bolus would be hidden and ignored in BOB calculations.

Most carbs raise the glucose for only a 1 to 2.5 hour period, though foods that are complex, fibrous, or contain more fat and protein will raise the glucose more slowly. The typical rise in glucose from carbs is much faster than insulin action and helps explain why post-meal spiking is so common.

A User May Be Tempted To Shorten The DIA Because:

- A bolus calculator’s recommended boluses are not preventing highs nor bringing highs down because basal or carb doses are too small, as seen in about 66% of those on pumps.7

- Shortening the DIA SEEMS like an easy way to increase bolus size compared to raising basals or lowering a carb factor.

- The actual time that boluses lower their glucose is hidden because the tailing action of prior boluses is hidden as it replaces the low basal rate.

Someone may be tempted to select a short DIA of 2 or 3 hours for their bolus calculator because they believe their insulin works quickly. In the recent past, someone may have taken a bolus and gone low 30 minutes later because a previous bolus was still working. They start to believe their insulin works really fast when in reality insulin stacking caused by its slow action caused the low. Or their basal rate or long-acting insulin dose may be too high, or they may have taken a meal bolus and gone low an hour later because the meal had foods with a low glycemic index or they overestimated how many carbs were in the meal. Many circumstances unrelated to the true DIA can make insulin seem “fast”.

Short DIA times in a bolus calculator, such as 2 or 3 hours, hide residual bolus insulin activity, cause unrecognized insulin stacking, and introduce other setting errors as the user attempts to compensate for the hidden bolus stacking. For example, when a 3-hour DIA is selected, a breakfast bolus given at 7 a.m. appears to have no residual activity past 10 a.m. If a high reading occurs at that time, more correction bolus insulin than needed will be given. The recommended lunch bolus will also be excessive. By late afternoon and evening, stacking can become a very big problem. The hypoglycemia that follows makes the basal rates appear too high since the pump says “active insulin” is zero. As a consequence, the basals may be incorrectly lowered and the carb factor number strengthened (lowered) to give larger carb boluses. When basal rates are too low, the carb and correction factor numbers have to be lowered to get sufficient bolus doses during the day to replace the missing basal.

A Short DIA Time Hides Your True BOB And:

- Causes “unexplained” lows as the bolus calculator recommends larger boluses than are really needed.

- Leads to incorrect insulin adjustments as basal doses are lowered, and carb and correction factors raised to compensate for the excess boluses.

- Causes you or your physician to lower (strengthen) carb and correction factor numbers to offset the missing basal.

- Causes more hypoglycemia when large carb boluses are given for high carb meals.

- Causes highs when meals are eaten late or skipped due to the low basal.

- Makes you override or not use your bolus calculator.

Unrecognized bolus stacking causes the pump user to lower their basal insulin delivery and lower (strengthen) the carb and correction factor numbers to get enough bolus insulin to cover their missing basal. This creates a basal/bolus imbalance. With a low basal delivery and strong carb and correction factors, low readings may occur whenever they use these strong factors, such as 1u/8 grams rather than 1u/10 grams to cover a high carb meal, or a stronger correction factor is used to lower an unusually high glucose.

Reducing the basal rates and covering missing basal delivery with a stronger carb factor works only as long as carb intake remains relatively consistent. A low carb meal (and smaller carb bolus) reduces the basal replacement and leads to higher BG readings, while a large carb meal could cause hypoglycemia.

We discourage short DIAs because they hide true bolus insulin activity and in many situations can be dangerous. For example, a child may have a glucose of 120 mg/dl (6.6 mmol) at bed with a large bolus taken 3 hrs before. If the DIA in the pump is set to 3 hours, a parent may think it’s OK for their child to go to sleep without a snack because the pump says “zero” for BOB. The basal then gets blamed for the low that follows, and wacky readings become more common. Unless the source of these problems is recognized as a DIA that is too short, unexplained glucose control problems continue.

When a pump does not seem to give enough bolus insulin, rather than shortening the DIA, look for the real reason: a total daily dose (TDD) or basal rates that are too low, or a carb factor number that is too high If your boluses do not give enough insulin for meals or high readings, don’t shorten a realistic DIA to increase bolus doses. Instead, lower your carb or correction factor numbers or raise your basal rates!

Today’s pumps offer a wide range of DIA times between 1.5 and 8 hours. This range was chosen to handle faster insulins (not yet available), as well as Regular insulin that was first used in 1922. However, the range is much wider than needed for current insulins. The time over which a carb or correction bolus lowers the glucose can vary from person to person. One study conducted by Novolog found about a 25% variation in action between different users.8 If we assume an average duration of 6 hours including the tail, the variation between different pumpers would be 5 hours and 15 minutes to 6 hours and 45 minutes, rather than 1.5 to 8 hours. Although DIA times vary from person to person, the differences are usually not that great.

Should I Change My DIA Time?

No. If your current DIA is 2, 3, or 8 hours, don’t change this without discussing it with your physician. You may need to change your basal rates, carb factor, and correction factor at the same time. Do not change the default setting or your current DIA time without discussing it with your doctor because your DIA may be directly related to other pump settings.

Linear Versus Curvilinear DIA Measurements

A BC measures residual bolus insulin activity either linearly (ie, 20% per hour for a 5 hour DIA) or curvilinearly. The curvilinear method more closely approximates insulin’s delayed onset of action and its gradual tailing off of residual insulin activity. Realistic DIA times for today’s insulins range from 4.5 to 5.5 hours for BCs like the Insulet patch pump that uses a linear approach, while DIA times of 5 to 6 hours are more appropriate for curvilinear systems that include insulin’s tailing activity like the Animas and Medtronic pumps.

DIA Time Recommendations

We recommend that people using bolus calculators keep their DIA time long enough to account for the actual impact of residual BOB. With a BC that calculates DIA linearly (Omnipod), select a time between 4 hours and 30 minutes to 5 hours and 30 minutes (see the graph of Humalog action to the right). For a BC that calculates DIA in a curvilinear fashion (Animas and Medtronic), select a time between 5 and 6 hours.

KEEP IN MIND, current pumps DO NOT subtract BOB from carb boluses, so all carbs get covered irrespective of any DIA setting or BOB measurement in the pump. (Animas does subtract once they go below the target range, and the Accu-Chek Combo (available in Europe) does the same.)

Physical Activity

In general, DIA does not vary greatly from person to person, nor in the same person from day to day. However, physical activity may impact the DIA. It does not directly shorten DIA but can shift glucose more rapidly into cells independent of insulin activity and can also increase blood flow around the infusion/injection site to speed up insulin transport. Both of these cause glucose levels to fall more rapidly. However, the DIA time should not be shortened for occasional increases in physical activity.

Children Compared To Adults

The use of a realistic DIA in children is especially important. Because children eat so often, the action time of a bolus or injection often overlaps two, three, or four meals or snacks, and complicates BOB calculations. It is essential not to stack or hide bolus insulin in children, even though the small insulin doses that children require often convinces parents that their child’s insulin works fast rather than that they might have received a half unit too much of it.

Dr. Bruce Buckingham, a pediatric endocrinologist at Stanford, looked at how quickly rapid insulins worked in children less than 7 years old and was surprised to find that rather than working quickly, their insulin seemed to work slightly slower than in published reports for adults. Two other research studies have looked at DIA times in kids and adults and found no difference (5.5 to 6.5 hours in both).9

In another study done by Novo-Nordisk of 18 children and adolescents between 6 and 18 years of age, the researchers concluded that: “The relative differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in children and adolescents with Type 1 diabetes between NovoLog and regular human insulin were similar to those in healthy adult subjects and adults with Type 1 diabetes.“ Although children use smaller boluses, the size of their boluses relative to their weight is not terribly different from adults. For example, a 2-unit bolus for a 50 lb. child and an 8-unit bolus for a 200 lb. adult is the same size relative to weight, and the DIA of each bolus will be the same.

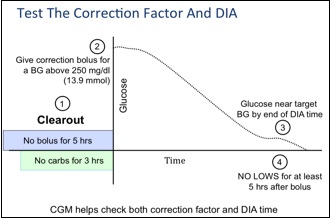

How To Test The DIA

Figure 3

Your DIA can be tested at the same time as your correction factor, as shown in Fig. 3, after a clearout period where no bolus is given in the previous 5 hours and no carbs are eaten for 3 hours. With no carbs or bolus insulin affecting the situation, and as long as the basal rates have been tested to keep the glucose flat when fasting, how long a bolus takes to bring the glucose down (your DIA) and how many mg/dl or mmol your glucose falls per unit of insulin (your correction factor) can be measured at the same time. The test should be performed at least three times to ensure accuracy.

DO NOT reset your DIA without discussing it first with your physician!

Select your DIA time based on research – DON’T change your DIA to fix control problems!

References:

- Walsh J, Wroblewski D, and Bailey TS: Disparate Bolus Recommendations In Insulin Pump Therapy, abstract, Amer. Assoc. of Clin. Endo. Meeting, 2007

- Mudaliar SR, Lindberg FA, Joyce M, Beerdsen P, Strange P, Lin A, Henry RR. Insulin Aspart (B28 Asp-Insulin): A Fast-Acting Analog of Human Insulin. Diabetes Care 1999;22:1501-1506.

- Heise T, Weyer C, Serwas A, Heinrichs J , Osinga J, Roach P, et al. Time-action profiles of novel premixed preparations of insulin lispro and NPL insulin. Diabetes Care 1998;21:800-803.

- Johnson MD, White JR, Campbell RK: Insulin therapy in the era of insulin analogs. U.S. Pharmacist 1996; 21: HS35-HS44

- Heinemann L. Time-Action Profiles of Insulin Preparations. Kirchheim; 2004.

- Howey DC et al. Diabetes 1994; 43: 396-402.

- Homko C, Deluzio A, Jimenez C, Kolaczynski JW, Boden G: Comparison of insulin aspart and lispro: pharmacokinetic and metabolic effects. Diabetes Care 2003 Jul: 26(7): 2027-31

- Walsh, R Roberts, and T Bailey: Guidelines for Insulin Dosing in Continuous Subcutaneous Insulin Infusion Using New Formulas from a Retrospective Study of Individuals with Optimal Glucose Levels Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology, Volume 4, Issue 5, pgs 1-8, September 2010

- B.A. Buckingham, J. Block, D. Wilson, K. Rebrin, G. Steiln: Novolog Pharmacodynamics in Toddlers. Diabetes 54 (Suppl 1): Abstract 1889-P, 2005.

Read Pumping Insulin for easy steps on how to succeed with your insulin pump.